The acronym OCD gets tossed around more casually than “amiright” in Instagram captions. People think of it as a catchall for cleanliness, orderliness, and fear of germs or contamination of any kind. But being methodical about, say, loading the dishwasher doesn’t mean you’re “so OCD.” The signs of OCD in adults are much more debilitating.

True obsessive-compulsive disorder is far from some quirk or fastidious personality trait—it’s a complex condition that controls your thoughts and behaviors. It may leave you feeling as if you can never relax, or like you need to white-knuckle your way through the day.

How the Signs of OCD in Adults Are Different from “I’m Sooo OCD”

Affecting between 2 and 3 million adults in the U.S., OCD is a mental condition where unwanted, intrusive thoughts, called obsessions, pop into your head and compel you to repeat behaviors, called compulsions, over and over, according to the International OCD Foundation.

You might wash your hands repeatedly, analyze a past conversation over and over, or perform counting rituals while walking up stairs. Everyone exhibits some of this behavior from time to time. (Did I leave the curling iron on?) But OCD manifests so intensely that it disrupts daily life, messes with relationships, and can consume hours each day.

GOTTA READ: 7 Things to Know If You’ve Just Been Diagnosed With OCD

There’s no gender gap with OCD in adults, except that onset tends to appear later in women—around adolescence or young adulthood. We don’t really know why that is, says Gerald Nestadt, MBBCh, MPH, director of the OCD Clinic at Johns Hopkins University. But research suggests that in certain cases, OCD may indeed be present in childhood, yet go unnoticed.

“I wasn’t diagnosed with OCD until my 20s, but looking back, when I was in elementary school I used to regularly pick fuzz out of my bedroom carpet and store it in boxes in my closet,” says Michele LeClerc, a New York writer now in her 40s. “It sounds like serial-killer behavior! But now I see it was probably the early signs of OCD.”

Which Brings Us To… the Actual Signs and Symptoms of OCD in Adults

OCD typically involves both obsession symptoms and compulsion symptoms, though it’s possible to experience just one or the other. Symptoms can range from mild to severe—as much as eight to 12 hours of the day—and come and go over time, getting worse during periods of stress, pregnancy, depression, or when you’re premenstrual, says Dr. Nestadt.

OCD exists on a spectrum, from high-functioning people who are troubled by intrusive thoughts but able to manage, to those who struggle to hold down a job, have a healthy relationship, or even leave their house. Symptoms may also get worse during major life changes, such as moving away from home to go to college, says Dr. Nestadt.

Obsession Symptoms

OCD obsessions are repeated, persistent, unwanted thoughts, urges, or images that just blast into your head. “In the general population, people have thoughts very similar to those that people with OCD have,” says Martin Antony, Ph.D., a professor of psychology and OCD expert at Ryerson University in Toronto. “The difference is most people ignore them. They’re not afraid of the thought, and they don’t think the thought means they’re bad.”

People with OCD, however, take the thoughts seriously. These obsessive thoughts typically fall under certain themes:

- Fear of contamination or dirt: fear of being contaminated by touching objects others have touched, or of things you may perceive as containing harmful germs

- Struggling to tolerate uncertainty: doubting you’ve locked the door or turned off the stove

- Needing things orderly and symmetrical: intense stress when objects aren’t in their place

- Violent or aggressive thoughts about harming yourself or others: fear that you’ll stab a family member or drive your car into a crowd, even though you would never

- Unpleasant sexual thoughts: fear that you’re a pedophile, when you aren’t

Compulsion Symptoms

Some people with OCD don’t have compulsions, but many do. They involve rules or rituals as a way of coping with the anxiety that stems from the obsessions—though often, they’re not related to the problem they’re supposedly addressing. For example, you might believe if you don’t touch an object a certain number of times, someone close to you will die.

Like obsessions, compulsions have themes:

- Washing and cleaning

- Checking

- Counting (this can also include having to always eat, say, five, not four, Cheez-Its or cherries or whatever it is you’re having)

- Orderliness

- Following a strict routine

- Seeking reassurance (for example, asking your partner 20 times a day, “I’m not a pedophile, right?”)

Some compulsions don’t show up as physical actions but instead as mental compulsions, such as rumination (reviewing and re-reviewing an event trying to “solve” it so you can get relief from the anxiety and uncertainty), says Kimberley Quinlan, LMFT, a cognitive behavioral therapist who treats OCD patients.

This can look a lot like run-of-the-mill anxiety, but people with OCD tend to ruminate with a greater sense of urgency, and it’s usually very distorted and catastrophic in nature, Quinlan says. For others with OCD, guilt can become a mental compulsion—where you go over and over in your mind something you did (or didn’t do) years, even decades, ago, to try and prove you’re not a “bad” person.

Other mental compulsions include repeating mantras over and over, as well as “mental hoarding,” where you’re trying to remember events exactly as they occurred, Quinlan explains. “People do this in hopes of getting some certainty or to reduce or remove their anxiety or doubt,” she says. But the relief is short-lived and only ends up reinforcing the behavior, encouraging it to persist.

This gets at a fundamental part of OCD: the need to be 100% certain. “If there’s an eighth of a percent chance it’s true—it’s true,” Dr. Nestadt says.

Why Do I Have This? What Causes OCD?

Like most mental health conditions, OCD results from a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Genetics

The closer you are biologically to a person with OCD, the more likely you are to have the condition, too. According to Dr. Nestadt’s research, if you have an identical twin with OCD, you have a 40 to 50 percent chance of developing the condition. Other first-degree family members have about an 8 percent risk—roughly eight times higher than in the general population, says Dr. Nestadt.

Brain Function

Researchers have linked OCD with specific neurotransmitters. (a.k.a. chemical messengers) and structures within the brain.

You’ve probably heard of serotonin—the so-called happy chemical that stabilizes mood. As with other anxiety-related disorders, people who have OCD tend to have low levels serotonin.

Another neurotransmitter called glutamate—a brain chemical that “excites” the neuron and causes it to fire off a message—has been found in high levels in OCD patients, which may explain why you can’t just calm right down after an intrusive thought. While peeps without OCD would be able to dismiss the thought and move on, those with OCD get more and more anxious about it.

Beyond neurotransmitters, certain brain structures may be involved, says Dr. Antony. These include the prefrontal cortex—an area that helps regulate cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning—and the basal ganglia, which, as they say on LinkedIn, has a real bias to action: planning actions to achieve a goal, executing habitual actions, and learning new actions in novel situations. Some evidence implicates basal ganglia dysfunction in OCD.

Speaking of action, in research from the University of Michigan Medical School, people with OCD showed greater brain activity than healthy individuals in areas involved in recognizing that they’re making an error—but less activity in areas that could help stop them from taking action in response. Meaning: an overreaction to errors may overwhelm your ability to tell yourself to stop.

Learned Behavior

Children who have a genetic predisposition for OCD may learn obsessive fears and compulsive behaviors by watching and modeling family members, says Dr. Antony. If you’re a parent, you may want to explain to your kids that what you’re doing isn’t the “norm” or something you want for them.

Trauma

Traumatic or stressful events may trigger OCD in those who are genetically predisposed. For example, Dr. Antony once had a client who developed contamination fears after his child caught a serious contagious illness, forcing the whole family to wash their hands repeatedly.

Pregnancy and Postpartum

Recent data indicates that over 15 percent of women experience OCD during the perinatal period, which can trigger the condition for the first time or worsen pre-existing symptoms. When Atlanta-based Alexandra Reynolds gave birth to a son with a rare food allergy, it kicked her OCD into high gear. Every night, she’d be on her hands and knees in the kitchen scrubbing the floor to get every potential crumb, and cleaning the kitchen and dining area immediately after eating. “We couldn’t eat at the same table as my son because I was so afraid of him grabbing something and putting it in his mouth,” she says.

How OCD Affects Work, Love, and Friends

OCD can color every aspect of adult life, says Elizabeth McIngvale, Ph.D., LCSW, director of the McLean OCD Institute in Houston, who treats OCD patients and has OCD herself. Let’s take work: Intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors can distract you from what you need to do, or keep you from meeting deadlines.

You may worry that you’ve unintentionally harmed a coworker. Or you may have a sexual thought about a colleague and worry that means you’re not attracted to your partner. Those with something called “just right” OCD, adds Dr. McIngvale, may feel that an email to their boss must be written perfectly, reading and rereading it for an hour before hitting send.

Romantic relationships can also suffer. “As soon as I started to get attached, or feel like ‘Oh, this is going somewhere good,’ OCD would instill doubt into the relationship,” Alexandra Reynolds (now married) says of her dating days. “It made me think questions like, ‘What if he doesn’t really like me that much?’ Or, ‘What if he’s lying to me?’ Or, ‘Gosh, I didn’t enjoy that kiss very much. What if that means I’m not attracted to him?’” (This type of obsessional thinking is sometimes referred to as relationship OCD.)

As a result, Reynolds would become ambivalent or overly clingy. Not only that, but because her OCD often stressed her out, partners would get frustrated with her nervousness and rigidity.

Depending on your type of OCD, sex can also prove challenging—with fears of contamination, intrusive thoughts, or compulsive rituals spoiling the mood for both of you.

How OCD Feels, According to Women Who Have It

“It feels like having this monster on my back or over my shoulder—telling me what to do, and how to feel, and what to think, and when to panic. And it always wants me to panic.” —Alexandra Reynolds, 41, a stay-at-home mom in Atlanta

“I’ve missed school field trips and outings with friends due to contamination fears. It feels like a constant tug of war between what I want to do, and what my OCD wants me to do—like my OCD is trying to rip my passions and values away, saying ‘oh, no, you actually don’t love those things,’ or ‘those things suck.’ And then it turns into a lot of missed experiences and opportunities that build up over the years.” —Caroline*, 23, a student in Boston

GOTTA READ: The Unexpected Way OCD Can Tank Your Mood

“OCD can wax and wane, but it’s always present to some extent, humming in the background. You can be having a perfectly wonderful day, and then all of a sudden, it pops up out of nowhere.” —Adira Weixlmann, 33, a San Francisco graphic designer

“OCD literally feels like you’re going to be eaten by a bear, and you have to act right now, to protect yourself, to protect others, to protect whatever it is that’s important to you,” —Katie O’Dunne, 31, an Atlanta-based faith leader

*last name withheld

So, Please, Let’s Talk About OCD Treatments

Although there is no cure for OCD, treatments can go a long way in helping you manage the condition and alleviate symptoms.

Medication

Because chemical imbalances in the brain are a big OCD factor, antidepressants and other medications that affect brain chemistry may be prescribed to treat it.

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) This type of antidepressants are the first meds you’ll likely be prescribed. They’re the same drugs commonly used for depression, and up until recently, we all talked about them working by increasing the levels of serotonin in your brain; while a new review debunked that and researchers aren’t sure exactly how SSRIs work, they simply do for many people. For OCD, SSRIs tend to be prescribed in higher doses and take longer to kick in, sometimes up to 12 weeks. Commonly prescribed SSRIs include:

• Fluoxetine (Prozac)

• Fluvoxamine (Luvox)

• Paroxetine (Paxil)

• Sertraline (Zoloft)They aren’t without their detractions: In one study, about 40 percent of people on SSRIs reported having side effects, the most common being sleepiness, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction (such as difficulty getting aroused or a loss of interest in sex). But if you can stick it out, some side effects—like anxiety and dry mouth—do tend to diminish within weeks, Dr. Antony says. And you can always talk to your doc about trying a different drug, or a different dose, or taking it at a different time of day.

- Clomipramine If you don’t respond to SSRIs, another medication that may be prescribed—or added to your SSRI—is clomipramine (Anafranil), a tricyclic antidepressant that also acts on serotonin. While clomipramine has been approved by the FDA to treat OCD, the side effects can be harmful—which is why most docs don’t start with it. Side effects can include seizures, depression, and suicidal thoughts.

- Antipsychotics Traditionally used to treat psychosis (but also conditions like bipolar disorder and depression), antipsychotics may enter your pill box. While experts aren’t exactly sure why antipsychotics, such as risperidone (Risperdal) and aripiprazole (Abilify), help in OCD, “there is evidence that they can boost the effectiveness of SSRIs for individuals who do not respond completely to SSIRs alone,” says Dr. Antony. You’d get a low dose, with possible side effects including cold symptoms, insomnia, and blurred vision.

Psychotherapy

Effective therapy can help calm overactive brain circuits in adults with OCD. (Gimme!) Two forms of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) regularly used for OCD include:

- Exposure Response Prevention (ERP) This type of CBT is considered the gold standard for OCD (OMG, brb when we think of yet another abbreviation, ‘k? LOL). Research shows exposure response prevention helps up to 70 percent of the time, and some evidence finds it may be more effective long-term than medication.

In ERP, patients are asked to do things that trigger obsessive thoughts (that’s the “exposure” part)—starting with the least severe and, over time, working up to the most severe—and then refrain from engaging in the compulsive behavior (the “response prevention” part.)

“We have people touch things that [they perceive to be] contaminated and then not wash their hands,” says Dr. Antony, “or leave their homes without checking to make sure they turned everything off.” If you do the behavior anyway—because this is hard and slip-ups happen (hi, human!)—you simply go back and repeat the “exposure” step again. “Over time, people learn nothing bad happens, and they become less and less anxious in those situations,” Dr. Antony says.

Likely, your therapist will walk you through this in a session and you’ll practice on your own at home, says Dr. Antony, with results taking 12 to 14 weeks. One woman we spoke with said she lives an “ERP lifestyle”: When her OCD is triggered, she uses it as an opportunity to employ ERP.

- Cognitive Therapy Some evidence suggests that adding another type of CBT—lose the “B,” and you get cognitive therapy—to ERP can improve results. This therapy is all internal work, where you’re encouraged to reappraise your beliefs around your intrusive thoughts. “If I have the belief that my intrusive thought is important, I might be encouraged to question that,” says Dr. Antony. “What evidence do I have that the intrusive thought is important? Is there evidence that I don’t need to pay attention to it?”

- Mindfulness and Acceptance Therapies While it’s still being researched, mindfulness has been shown to be helpful as a supplemental treatment for OCD. How it helps: Mindfulness-based therapies teach you how to be more present and aware in the moment, encouraging you not to control your thoughts or emotions but rather just let them happen. You’re also asked to take stock of your values: What’s important to you? What changes must you make to lead a life more consistent with your core values?

Although most with OCD are helped by the first-line treatments above, some 30 to 40 percent have only slight or no improvement, says Dr. Nestadt. There are other medications and more intense therapy programs to try, and people with severe cases of OCD may be candidates for procedures, including brain surgery (destroying tissue in areas linked to OCD in an effort to alleviate symptoms), deep brain stimulation, and transcranial magnetic stimulation—the latter of which has recently emerged as a promising and less-invasive option for treatment-resistant OCD, says Dr. Nestadt.

3 Things You Should Never Say to a Person With OCD

It’s ok to suggest a friend or loved one to seek help for their OCD. It’s not cool to belittle, shame, or condescend. So inform yourself, and keep the following outta your conversations.

1. “You should see my mom’s kitchen—she’s so OCD!”

People often use the term “OCD” as slang for someone who’s very neat or likes things a certain way. But OCD is not an adjective, says Dr. McIngvale. “We’re not talking about somebody who cleans their house once or twice a week. We’re talking about individuals who are stuck cleaning for hours on end.”

Instead, say… Um, nothing. Unless your mom has legit diagnosed OCD.

2. “Fine, I’ll wash my hands.”

Peeps with OCD often try to pull family members into their struggles—they may ask them to sanitize things, or wear clean clothes, or shower after returning home from the subway. Or they may seek reassurance, asking the same question again and again: “Is the door locked?” “Am I safe?” “Am I a good person?” It’s natural to want to reassure someone you care about, but unfortunately doing so enables the OCD, says Dr. Nestadt.

Instead, say… “I’ve noticed you are regularly repeating XYZ behavior. Have you considered seeing a therapist?” If they’re already in treatment, offer support by saying something like, “I love you, but I don’t love your OCD. So I’m not going to answer that question,” Dr. McIngvale suggests. If you’ve found yourself heavily involved in their obsessions, their therapist may want you to come into a session to discuss how to handle it moving forward.

3. “Let’s just use logic.”

Most people with OCD know they’re being illogical but can’t help it, says Dr. Nestadt. So trying to reason with them won’t do any good.

Instead, say…When Alexandra Reynolds is in the midst of a severe OCD episode, her husband has learned not to interrupt her, but rather communicate with her. “He’ll let me know, ‘Hey, I think this might be your OCD. You may want to cool off.’ Or he’ll say, ‘We’re going to go outside and give you some time.’” Sometimes he’ll put on one of their son’s hand puppets—a purple one they call OC monster—and say in a monster voice, “I think it’s me!” Says Reynolds, “It’s so ridiculous that it makes me laugh and pulls me out of that anxious state.”

Related Conditions to OCD

Comorbidities: The word sounds dire, but it jut means that one condition shares similar traits with, and can sometimes occur alongside, other mental health conditions. One study suggests that most adults with OCD—about two-thirds—have at least one other psychiatric disorder. (Oh joy.)

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD)

Sometimes confused for OCD, OCPD is an overwhelming need for order and perfection, says Dr. Antony. (How could these be confused, said no one ever.) The difference when you’ve got the added “P”? You truly believe your way is the right and best way, and you’re totally fine imposing your rules on others. (Think of Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory, says Dr. Antony: “This is my seat and nobody else can sit in that seat.”)

People with OCD, by contrast, are usually aware that their thoughts are unreasonable That said, you can have both conditions: One study found that in a sample of 148 people with OCD, nearly half also had OCPD.

Anxiety

Anxiety disorders and OCD love hanging out and watching sunsets together: OCD was even considered an anxiety disorder until recently. About 6 percent of the general population has a generalized anxiety disorder, compared with nearly one-third of adults with OCD.

Depression

Major depression—a severe form of depression—commonly tags along with OCD, affecting at least one-third of OCD patients. Most people with both conditions say that the OCD came first, suggesting that depression may be a response to the OCD fallout on relationships, school, work, life.

Trichotillomania (hair-pulling disorder)

When you have trich, you’ve got an irresistible urge to pull out your hair, literally—from the scalp, eyelashes, eyebrows, or pubic area—often leaving behind bald spots. Research suggests that OCD occurs in more than a quarter of patients with trichotillomania.

Dermatillomania (also called excoriation, a skin-picking disorder)

Dermatillomania is similar to its cousin, trich, but instead focused on picking at skin—from the face, head, cuticles, or anywhere—to the point where skin may bleed or bruise. The urge to pick over and over can be a response to recurrent thoughts about skin, or as an attempt to bring relief from sadness, anger, for stress.

Others pick because they’re bored. Some pick…well, just because. They might be bored. About a quarter of people with skin-picking disorder also have OCD. Michele LeClerc, the writer with OCD, picks along her inner ears until they bleed, then picks at the scabs—and has no idea why she does so other than it’s oddly satisfying.

Tics

OCD and tics—besties! (Unfortunately.) Tics are sudden twitches, movements like eye blinking or shoulder jerking, or sounds like throat clearing, sniffing, or grunting, that people do repeatedly and involuntarily.

They occur so often with OCD that “tic-related OCD” was actually added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 2013. Research suggests this tic-related subtype may account for as many as 40 percent of OCD cases diagnosed in childhood or adolescence.

Eating Disorders

Conditions like anorexia, bulimia, and body dysmorphia are sometimes associated with or even confused for OCD. Dr. Antony once got a referral for a client who was thought to have OCD, with food obsessions and binging-and-purging compulsions; she turned out to have bulimia instead. Still, eating disorders can occur in those with OCD, and vice versa. Some 10 to 17 percent of OCD patients also have an eating disorder.

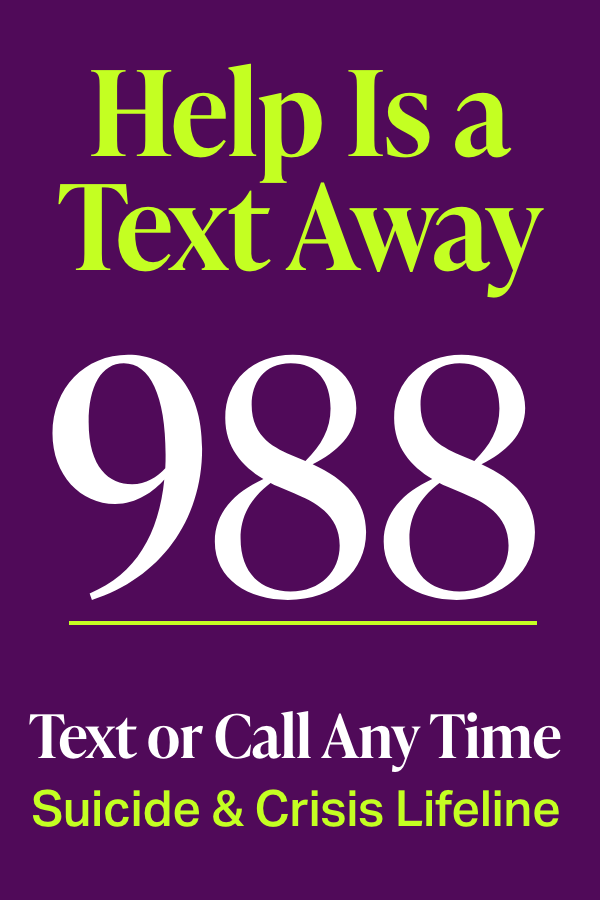

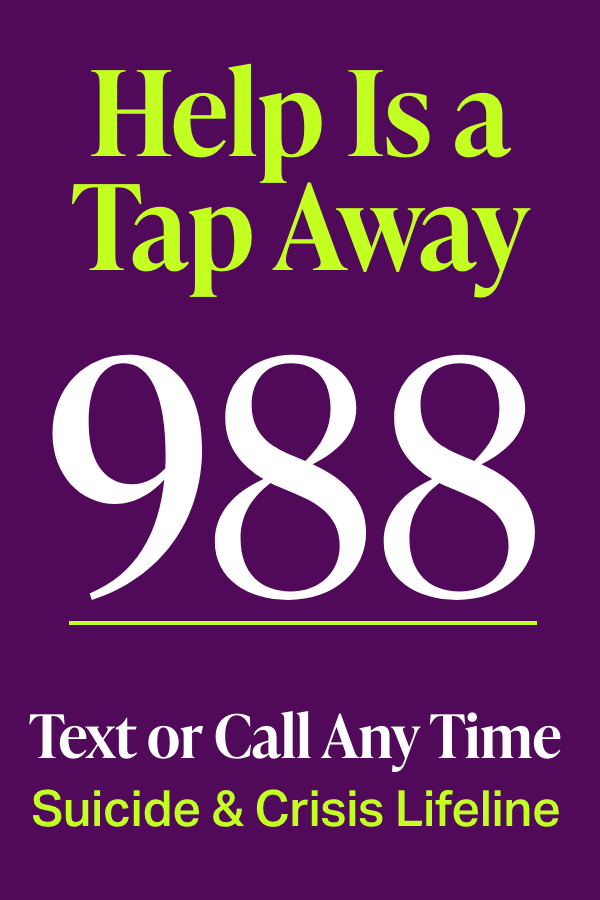

Where Can I Find Help?

Whether you’re looking for a provider for the very first time or just looking to feel less alone, these platforms are your friends.

The Orgs

International OCD Foundation. This global organization has been serving people with OCD for more than 35 years. Visit their site for insights and advice from OCD experts; therapist and clinic directories; and tips for finding the right therapist for you.

A Penny for Your Intrusive Thoughts. You can read others’ intrusive thoughts—and anonymously share your own—as a reminder that you’re not the only person in the world who feels this way.

Hard Quirk. Founded by two “queer creatives” (Ali and Maia) who have personal experience with OCD, Hard Quirk provides the OCD community with education, awareness, and myth busting. Register for virtual support group meetings, facilitated every other week by the founders.

The TLC Foundation. Body-focused repetitive behaviors—like hair pulling and skin picking—are different from but related to OCD, and many OCD patients have them. Find a therapist, support group, and all kinds of helpful info.

The Follows

Kimberley Quinlan, LMFT, @youranxietytoolkit

Follow because: Her IG feed mixes relatable, fun hits with science-backed education and advice that you can apply to your life. Plus, the accent.

Alexandra Reynolds, @alexandraisobsessed

Follow because: One of the few Latinx OCD Instagrammers out there—important to note, since mental illness is often stigmatized in the Latinx/Hispanic community.

Reverend Katie O’Dunne, @revkrunsbeyondocd

Follow because: Katie’s education in faith and personal experience with OCD uniquely qualify her to help others on their spiritual and mental health journeys.

OCD Doodles by Laura, @ocddoodles

Follow because: These playful “infodoodles”—created by Laura, who has OCD—share advice and inspiration. Enjoy ’em for free in your IG feed, or purchase one in her Etsy store—20 percent of proceeds are donated to OCD Action.

Elizabeth McIngvale, Ph.D., LCSW, @drlizocd

Follow because: A therapist who also lives with OCD, Dr. Liz shares her personal and professional experience.

Lauren Rosen, LMFT, @theobsessivemind

Director of The Center for the Obsessive Mind

Follow because: She explains it better than almost anyone we’ve spoken with, and she’s a realist—she knows you aren’t going to give up your compulsions with a finger snap.

Yasmin, @theteaonocd

Follow because: She mixes trending sounds and OCD. Or as her bio puts it: “aussie ocd sufferer making tiktoks as a coping mechanism lmao”

The Apps & Courses

NOCD: Effective care for OCD. This free app, with 4.8 stars, offers live video-based OCD therapy and in-between-sessions support and helps you get matched with a licensed OCD therapist in your state.

Breathe 2 Relax. Designed by the National Center for Telehealth & Technology, this free app teaches breathing techniques to manage stress and anxiety.

ERP School. This online course from Kimberley Quinlan, LMFT, teaches you how to do exposure and response prevention therapy. For $197, you get six hours of video instruction from Quinlan, five video modules on the main components of ERP, 18 video tutorials to ID and manage your specific OCD issues, and more.

What Is OCD?

OCD Symptoms and Causes

Relationship OCD

Glutamate and OCD

Basal Ganglia

Michigan Medicine Research on OCD

OCD and Pregnancy

Basal Ganglia Dysfunction in OCD

“Just Right” OCD: https://iocdf.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Just-right-OCD-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Sertraline Medication for OCD

SSRIs Optimal Dose for OCD

SSRI Minimum and Maximum Doses for OCD (1)

SSRI Minimum and Maximum Doses for OCD (2)

Fluvoxamine for OCD

Paroxetine for OCD

SSRI Side Effects

Antipsychotics

Risperidone for OCD

Antipsychotic Supplementation for OCD (Aripiprazole)

Antipsychotic Medication Side Effects

Therapy for OCD

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy outcomes for OCD

Adding Cognitive Therapy to ERP

Mindfulness for OCD (1)

Mindfulness for OCD (2)

Neurosurgery for Severe OCD

Deep Brain Stimulation for OCD

OCD and Other Psychiatric Disorders: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11994838/

OCD and OCPD: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22689335/

OCD and Anxiety: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3243905/

OCD and Depression: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3243905/

OCD and Trichotillomania: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6908854/

Dermatillomania Basics (1): https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/skin-picking-disorder/

Dermatillomania Basics (2): https://iocdf.org/about-ocd/related-disorders/skin-picking-disorder/

OCD and Dermatillomania: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7115927/

Tic Disorders Basics: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/tourette/diagnosis.html

Tic-Related OCD: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6203551/

OCD and Eating Disorders: https://iocdf.org/expert-opinions/expert-opinion-eating-disorders-and-ocd/