Picture this: You’re at Trader Joe’s, about to open the cooler door for a bag of frozen peas, when someone else gets there first. You mind begins to spin: If I touch that door handle, will I be contaminated? Should I sanitize right after?

Before the pandemic, this was easily a typical thought for someone with OCD.

Today, it’s easily a thought for an entire population without OCD. And the tricky part, in our world of COVID, is it might very well be a reasonable response, mental disorder or not.

“If I go to the store and see someone without a mask touching something, an adaptive response may be to not touch that thing or, if you do touch it, to put on some hand sanitizer,” says Susanne Ahmari, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, where she runs the Translational OCD Laboratory, and a member of the scientific advisory board for the International OCD Foundation.

Nobody wants COVID, obviously. “So it’s a question,” Dr. Ahmari continues, “of when is that an adaptive response and when is it a maladaptive response?”

It’s a fascinating question in these times, when stopping the spread of coronavirus is a public health priority, a preoccupation with cleanliness has become the norm, and we’re all scheduling appointments for our third booster.

It’s enough to make you wonder: Is the pandemic giving us all OCD?

Compulsions Gone Mainstream

For many people with obsessive-compulsive disorder—a mental condition where unwanted, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) pop into your head and compel you to repeat behaviors (compulsions) over and over—intense anxiety around germs is nothing new.

A common OCD subtype centers on contamination fears—which may include a fear of becoming ill or spreading illness to others—and if you’ve got this, you’ll often try to calm those fears by washing your hands or using sanitizer repeatedly, or avoiding close contact with others. In some cases, you may rarely leave the house at all.

But what COVID has sparked, along with its classic fever and sore throat, is a startling explosion of OCD symptoms in otherwise healthy people. In a review published in the journal Current Psychiatry Reports, which analyzed multiple studies on OCD during the pandemic, these stats appeared in people not diagnosed with OCD:

- A “significant” escalation in obsessive-compulsive symptoms in both 2020 and 2021 in U.K. adults

- A 3.5-11.3 percent jump in compulsive symptoms in China

- A 12 percent increase in Portugal, and a 21 percent rise in Germany, of “clinically elevated” OCD using the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory, a self-report of 18 items that assess OCD symptoms

This is all the more alarming, if not completely surprising, when you consider the general rate of OCD worldwide: 2 percent.

What’s either more or less bizarre, depending on how you look at it, were the findings of a study published in 2021 in The Lancet Psychiatry journal: People without depression, anxiety or OCD actually had a greater surge in depressive symptoms, anxiety, worry, and loneliness than those with a diagnosis.

So…huh? What’s it all mean? Will OCD symptoms persist, like effects of Long COVID, far after the pandemic finally wanes?

It’s complicated. OCD, like most mental health conditions, is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors—meaning a pandemic alone is unlikely to trigger the disorder unless a person is genetically predisposed. Only time will tell how many people who experienced COVID-related OCD symptoms will go on to develop actual OCD, especially since people often don’t seek treatment—and, hence, get a diagnosis—for years.

The OCD Brain

While these stats may be sending your mind in a tizzy, it’s worth noting that they were extracted via assessments, not brain scans. Corona anxiety and OCD can look similar on the surface, but they may function differently in the brain. According to Dr. Ahmari, research shows that, compared to those without it, people with OCD have greater activity in certain brain regions.

- Prefrontal Cortex: The front of the cerebral cortex (the brain’s outermost layer), key to decision-making, behavioral flexibility, and the ability to adapt—“those are areas of the brain that help you determine what actions you’re going to take, and in what situations,” Dr. Ahmari says. Overactivity in the prefrontal cortex has been associated with OCD, though ongoing research may uncover more nuance.

- Basal Ganglia: A group of structures found deep within the brain—including the striatum, which, kinda like Paulie Gualtiere on The Sopranos, is responsible for carrying out the actions your prefrontal cortex (or Tony) tells you to do.

- Thalamus: You actually have two thalami (rhymes with alibi, not salami), and each transmits messages to the cerebral cortex. “It’s classically been thought of as a kind of relay station, just passing signals through,” Dr. Ahmari says. “But we’re finding more and more that it seems to be really important also for helping to determine what we should do in a particular situation.”

Together, these three areas—the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus—form a series of connected circuits key for behavioral flexibility and action selection, Dr. Ahmari says.

In people with OCD, these circuits may rev up and barrel out of control like a runaway train, perpetuating a cycle of obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors, Dr. Ahmari says. With proper treatment, this brain activity tends to return to levels comparable to what you’d find in people without OCD.

Might those same overactive circuits also be lighting up in the general public, as we try to cope with corona anxiety and adopt OCD-like rituals?

We don’t have the data to say. But Dr. Ahmari’s speculation, based on clinical evidence, her experience in the clinical, and the literature on what OCD symptoms look like over time, is this: For a subset of the population, those rituals (particularly early in the pandemic) may have triggered hyperactivity—and “what I call a positive feedback loop where it goes out of control,” she says—in those brain regions right away, leading to lasting symptoms and new-onset OCD.

GOTTA READ: What Mental Readers Use to Manage Their OCD

“Then there are people who have the brakes on their system, and their brakes work,” she continues, “so they can switch and do things differently.” Translation: COVID rituals probably do not trigger that hyperactivity, and they won’t develop OCD. Further research is needed to figure out if this speculation is true.

So: Will You Develop OCD?

We’re guessing you won’t be having an MRI anytime soon, so here’s another clue: For people with OCD, the more they engage with obsessions and compulsions, the more set the cycle becomes and the harder it is to break free, Dr. Ahmari explains. This means they may have a harder time changing their behavior as new information is released and public health guidelines change.

“In the beginning of the pandemic, I was wearing gloves everywhere,” Dr. Ahmari says. “But as it came out that’s not really how COVID was transmitted, I stopped. So that’s one of the lines: Is this adaptive or not adaptive? If you can change your behavior in the face of evidence that says you don’t need to do this anymore, it’s likely adaptive. And if you can’t, it starts to veer into: Could this be OCD?”

In fact, research shows that OCD patients are more likely than others to form habits. “It’s like their brains are stickier,” Dr. Ahmari says.

In one study, participants with and without OCD were asked to press pedals, receiving a mild but unpleasant shock if they chose the wrong one. Once everyone learned which pedal to avoid, the researchers unplugged the shock machine, removing the threat of shock. Knowing this, many participants stopped avoiding the “wrong” pedal—but those with OCD were more likely to continue to avoid it, even though they knew nothing bad would happen if it were pressed.

“That’s the kind of thing you can imagine potentially translating to the real world,” Dr. Ahmari says. “We now know you don’t need to Purell yourself every time you touch something in the grocery story, but the person with OCD might say, ‘I know that logically, but I’m going to do it anyway.’”

Another way to think of adaptive versus maladaptive behavior is to assess whether it’s useful. Going back to that scenario in Trader Joe’s, someone without OCD should be able to touch that handle, grab the peas, and finish shopping—applying hand sanitizer at the end of the trip. For most, that will feel like enough to mitigate the risk and won’t disrupt their day very much.

“But what’s not useful,” says Dr. Ahmari, “is if every time you saw someone without a mask in a store you had to stop and hand-sanitize. Or do a ritual of wiping down every door handle you needed to open. That would take lots of time out of your day, and you might not even be able to complete your shopping, because this is giving you so much anxiety you have to go home.”

GOTTA READ: Uh Oh, Another Thing: Climate Anxiety

The thing is, we all get a little obsessive and repetitive sometimes. But for a diagnosis of OCD to be made, obsessions and compulsions must be so extreme that they consume a lot of time and interfere with important activities that you value, according to the International OCD Foundation.

For most people, the pandemic has caused many small moments of concern. But for Alexandra Reynolds, 41, from Atlanta, who struggles with contamination fears due to OCD, the pandemic felt like her worst fears were being realized.

“I felt like the entire world was completely unsafe,” she says. “I became afraid of the mail, afraid of packages, afraid of the groceries.” At the height of her panic, she banished her husband—whose job as an air traffic controller required him to leave the house to go to work—to the basement for 10 days.

To wit, the pandemic spawned its own condition, dubbed COVID stress syndrome, whose signature symptoms include danger and contamination fears, xenophobia, traumatic stress, socioeconomic concerns, and compulsive checking and reassurance seeking. In perhaps a slightly #duh finding, a study published in the Journal of Anxiety Disorders showed that people with anxiety-related or mood disorders were more negatively effected by this syndrome. And those with OCD, found another study, had worse COVID stress reactions than those with social anxiety disorder or specific phobias.

Caroline, a recent college grad who lives with OCD and asked us not to use her last name, describes new COVID-related compulsions—she would repeatedly check herself for COVID symptoms multiple times a day, taking her temperature, assessing herself for sore throat or runny nose, and even smelling objects to check her sense of smell. “If I’m at the grocery store or something, I’ll be like, let me smell, like, my T-shirt to see if I can smell the fabric softener,” she says.

The OCD Treatment Conundrum

The gold-standard treatment for OCD is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy called exposure response prevention—where patients are exposed to their fears and instructed not to do the behavior they normally would to ease their anxiety. For example, you would touch a door handle—or whatever object you fear—and then not sanitize your hands.

As you can imagine, the pandemic complicated this treatment. “All of a sudden, the therapist is like, well, so now you can use Purell—but you have to know it’s only because it’s adaptive in this situation,” Dr. Ahmari says.

Anecdotally, some OCD patients reported a sense of vindication when the pandemic hit—“almost like they knew what to do. Like, ‘Aha, my superpowers are of use!” Dr. Ahmari says, describing patients’ experiences.

Kimberly Quinlan, LMFT, a cognitive behavioral therapist in California, had a similar observation. “A lot of my patients have said it’s the first time they felt understood by the general community,” says Quinlan, an International OCD Foundation advocate. “Now other people are exposed to this real-life stressor, but that’s what it feels like for someone to have OCD—the feeling of having a worldwide pandemic is similar.”

Still, as the pandemic progressed and restrictions were lifted, many with OCD have struggled to reengage the brakes on those obsessive-compulsive behaviors, Dr. Ahmari says. One review found that up to 65 percent of people with OCD reported worsening symptoms during the pandemic, with contamination-related symptoms particularly affected.

Where We Go From Here

Whether or not you’re living with OCD, here are a few takeaways:

Let public health guidelines (not fear) guide your decisions. “Fear will have you locked up in your house, never going out, never living your life,” Quinlan says. Despite all the memes (and, yeah, they are funny), follow guidelines from the CDC or World Health Organization—don’t try to go above and beyond.

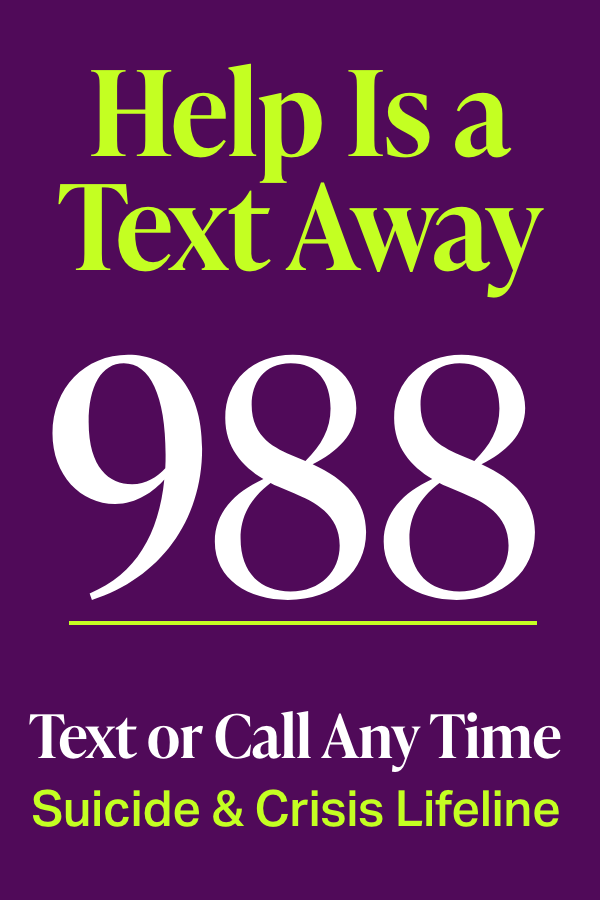

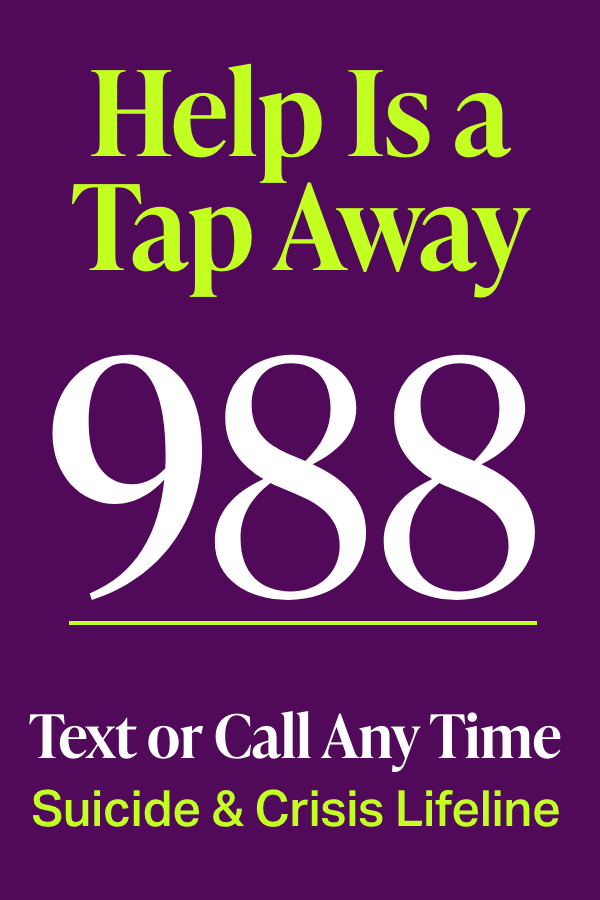

Ask for help. “Talk to your doctor if you’re having a high level of anxiety,” Quinlan says. The number of Americans reporting mental or behavioral health conditions has surged during the pandemic, the CDC reports. A formal mental assessment is key for proper diagnosis and treatment, Quinlan says.

Educate yourself on OCD. The disorder is not just a preference for things to be clean. “It’s this very isolating, very intrusive, very panicky feeling,” Reynolds says, “that if I don’t do this cleanliness thing or take this shower, or if I don’t have the right chemicals in my house to clean things, harm is going to befall someone I care about.”

The pandemic is not giving us all OCD, but hopefully it is giving us all a better understanding of it.

Geek Out on Our Sources

OCD Contamination Fears: https://iocdf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Contamination-Fact-Sheet.pdf

FDA Approval of Third Booster Shot: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-moderna-pfizer-biontech-bivalent-covid-19-vaccines-use

Study Review of OCD Symptoms During COVID: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-021-01284-2

Lancet Psychiatry Study: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33306975/

Worldwide OCD Rate: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9393390/

U.S. OCD Rate: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd

Basal Ganglia: https://www.britannica.com/science/basal-ganglion

Thalamus: https://www.britannica.com/science/thalamus

Habits and OCD: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3988923/

OCD Diagnosis: https://iocdf.org/about-ocd/

COVID Stress Syndrome: https://adaa.org/learn-from-us/from-the-experts/blog-posts/consumer/covid-stress-syndrome-5-ways-pandemic-affecting

COVID Stress Syndrome and Anxiety Disorders: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0887618520300852?via%3Dihub

COVID Stress Syndrome and OCD: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7746142/

Treating OCD During Pandemic: https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/managing-anxiety-and-ocd-during-a-pandemic/

Worsening OCD Symptoms During Pandemic: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8570941/

Mental Health Condition Surge During Pandemic: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6932a1.htm