“I hate it because I fall for it every year,” says Meirav Devash, of January’s inescapable four-word cultural theme. Now in her 40s, the Mental editor-at-large started binge eating and hiding food in her room when she was 12, and has been yo-yo dieting ever since. “New Year’s is the perfect time for these ‘new you’ messages because it’s when you, or at least I, generally feel peak disgust at my Halloween candy, Thanksgiving dinner, Christmas cookie, and Hanukkah latke bacchanalia.”

Devash’s thoughts and patterns mimic those of so many others with disordered eating, who get triggered by—and often succumb to—the promise of a “new you.” She’ll start a diet, lose weight, become more obsessive about food restriction and exercise, then burn out and gain back the weight, plus a little bit more. “I feel trapped in a cycle—just playing with the same weight up and down forever. I feel like a failure.” But the fallout of this experience isn’t just a mental one—it nearly killed her.

“The one year I didn’t make a resolution to lose weight was when I’d already lost enough to be a ‘New Year, New You’ story,” she explains. “I had lost 100 pounds and celebrated with a story at the women’s magazine I worked for,” which included a glam “after” picture shot by a famous fashion photographer.

By 2023 standards, the story title, “Disappearing Act,” was unfortunate. “It was an apt headline,” says Devash, “since my life had basically been reduced to personal training sessions and weird diet behaviors, like eating all my meals with chopsticks and obsessively checking how many steps I’d taken each day.” A self-described non-athlete and “more of a yoga person,” Devash (shown below) was lifting weights, swinging kettlebells, and strenuously running stairs to keep the pounds from returning.

She kept it up until, a year later, she was hospitalized with internal bleeding from varices (varicose veins) in her esophagus due to a condition she didn’t know she had, called portal hypertension. “One thing that causes varices to bleed?” she says caustically. “You guessed it: strenuous exercise.”

Is this what they mean by “New Year, New You”? Because it was indeed a new her. Just not a healthier one. And she’s far from the only one who’s suffered a much worse fate than being [insert hushed tone] overweight. People without pre-existing conditions can end up exacerbating them from what’s called “weight cycling”—where your weight regularly fluctuates by large amounts, often brought on by the back and forth of dieting.

“The diet industry perpetually sells the myth that our bodies are lumps of wet clay and that we are only ever a little willpower away from six-pack abs and perpetual bliss,” says Lauren Rosen, LMFT, director of The Center for the Obsessive Mind in California, an outpatient treatment center specializing in eating disorders and anxiety disorders. “And boy does the diet industry capitalize on New Year’s resolutions! All of the messaging around ‘New Year, New You’ makes bodies an easy target. Seeing so many people try to change their bodies and hearing people discuss how they’re going to lose weight can be very triggering for individuals in recovery [from eating disorders].”

And it sends some people into crisis. According to a first-of-its-kind 2021 study published in Psychosomatic Medicine, nearly 20 percent of people admitted into an eating disorder (ED) treatment facility attributed the onset of their ED to anti-obesity, pro-dieting messaging.

“‘New Year, New You’ exploits body shame and people’s desire for a renewed sense of self, reinforcing a core message that their bodies are not good enough, and that they have not been ‘disciplined’ throughout the year to lose enough weight to achieve society’s standards of thinness and health,” says therapist Shelby Castile, LMFT, founder of The OC Shrinks, a organization of 3,000 mental health professionals in Orange County, California.

Even obesity researchers wince when they hear the phrase. “Weight is tied to morality, character, and attractiveness in society. ‘New Year, New You’ messaging can make people feel negatively toward themselves and result in extreme actions in an effort to change,” says nutritional scientist Emily Dhurandhar, Ph.D., chief scientific officer at Obthera, which provides software and services for “evidence-based, personalized obesity management,” and interim associate editor for the International Journal of Obesity. “Those actions can easily lead to disordered eating patterns without sound guidance. And sometimes, those negative feelings lead down a difficult and unproductive road without any improvement in weight or health.”

And how. According to a study in the International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35 percent of “normal dieters” progress to “pathological dieting”—unhealthy eating behaviors like skipping meals and calorie restriction—and 20 to 25 percent of those individuals eventually develop eating disorders. That means for every dozen of your friends and family who are resolving to drop a few pounds in 2023, four will struggle to step off the diet train and one is likely to eventually develop a new eating disorder. New you, indeed.

How Did New Year Come to Mean New Body?

New Year, New You. It’s quick, punchy, intriguing—the stuff of marketing gold. And, as with real gold in an 1848 California stream, miners have been plentiful. Particularly in January, they include friends, family members, magazines, digital sites, social media posts, and a big ol’ percentage of ads for weight loss plans, fitness programs, and detox cleanses. “It’s sad. It’s harmful. It’s damaging the minds of the younger generation,” says Castille. “Unfortunately, I see it everywhere I turn.”

We all do. “New Year, New You” is omnipresent—from gyms to medical centers, universities to retailers, even the Cleveland Clinic and the NIH.

It’s hard to remember a time when starting the new year on a diet wasn’t A Thing, but certainly cavepeople didn’t subsist on berries and leaves each January to look svelte in their loincloths. To understand how “New Year, New You” became the month’s unofficial mantra, we must look at the evolution of resolutions themselves.

The first recorded New Year’s resolutions date back to 1672, when—in a January 2 diary entry titled “Resolutions”— Scottish writer Anne Halkett listed vows from biblical verses, such as “I will not offend any more.” On January 1, 1813, a Boston newspaper discussed how people were “beginning the new year with new resolutions and new behaviour” to “wipe away all their former faults.”

Somewhere in that century and a half, we humans shifted from communal do-gooding to personal reinvention. “January 1 is a secular date, but every religious tradition has an annual time to reflect on how to better achieve the ideals of our communities,” says medical and psychological anthropologist Eileen Anderson, Ed.D., founding director of the Medicine, Society, and Culture Center at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland.

Traditionally, these goals were centered around improving society. But over time, culture became more individualistic—and so did the new year goals people set. “It went from, How can I better meet the needs of my community, to How can I maximize myself and become a better me,” Dr. Anderson explains.

In 1947, America’s main resolutions, per a Gallup poll, still seemed to reflect a bit of both:

- Improve my disposition, be more understanding, control my temper

- Improve my character, live a better life

- Stop smoking, smoke less

Jump to 2023, and our top three desires exclude not just community, but character too. They focus instead, per Statista polls, on our bodies: exercise more, eat healthier, and lose weight. Each ranks higher than wanting to spend more time with family or friends, save money, or reduce job stress.

This is no coincidence. “Resolutions both reflect and reinforce social changes,” says John C. Norcross, Ph.D., distinguished professor and chair of psychology at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania who has conducted multiple studies on resolutions. “Americans tend to be individualistic and quite puritanical in resolutions. It’s largely what I’m personally going to do and largely framed as what I’m going to deny or force.”

Individual. Puritanical. Deny. Force. In many ways, these four words—much like “New Year, New You”—summarize just how dangerous weight loss resolutions can become.

Honey, I Shrunk the American Woman

We are a nation of dieters: According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 17 percent of Americans are on a “special diet”—which includes categories like low-fiber, high-protein, and gluten-free—at any point in time, up from 14 percent a decade earlier. The top special diet? Weight loss or low-calorie.

Beyond those on “special diets,” a consistent 60-plus percent of women have wanted to lose weight between 1990 and 2021, per annual Gallup polls. The data lags between the ’60s and the ’90s, but in 1957, that percentage was 20 points lower. (Ironically, over the same period, obesity rates in the U.S. rose from 30.5 to 41.9 percent.) So what happened?

Diet wasn’t always a dirty word. In ancient Greece, diatita referred to a way of life that included taking care of your physical and mental health. It wasn’t until the 19th century that people began “dieting for aesthetic purposes,” according to a 2016 literature review published in the Journal of Food Research. Along with the telephone, postage stamps, and A Christmas Carol, the Victorian era ushered in both fad diets and the industrial revolution.

And with that revolution came factory-made clothes—and with them, standardized dress sizes, creating physical comparison in a way that hadn’t previously existed. At the same time, scientists discovered the calorie and other nutritional components, making health quantifiable. And, according to historical gastronomist Sarah Lohman, as concerns rose about the internal-organ-damaging effect of corsets, their fashion caché tumbled—leaving women displeased with their natural waistlines.

“By the end of the century, Americans had fallen headfirst into this battle against fat,” Lohman said in a lecture at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. “Between 1890 and 1920 specifically, America’s image of the ideal body completely changed from one of healthful plumpness to one where fatness became associated with sloth.” What began to grow, continued the author of Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine, was “a surprisingly strong current of disgust against people who were perceived as obese.”

More specifically, American culture shifted from appreciating larger bodies to equating them with laziness and lack of self-control, misperceptions that studies show still persist today. “For many people,” says Dr. Anderson, “health replaced religion in terms of what’s ‘good’ or ‘bad.’” As health took on an increasingly moral value in society, “health” and “thinness” became, in the minds of many, interchangeable.

The media served as a megaphone for this anti-fat sentiment. Between 1901 and 1925, women’s bust-to-waist ratios in women’s magazines shrunk 60 percent, according to an analysis published in the journal Sex Roles. And as women tried to fit this new “thin” archetype, eating disorders rose starkly.

From there, weight loss companies and diets proliferated: 1950, the cabbage soup diet; 1961, the founding of Weight Watchers; 1977, Slim Fast; 1983, Jenny Craig; 1992, Atkins; 2003, the South Beach Diet; 2008, the launch of Noom; 2012, the proliferation of juicing; 2014, paleo. And—coming in on the very tail of U.S. News & World Report’s Best Diets of 2022 (meaning, they’re hardly “best” at all), keto, the Duke diet (think: all protein, all the time), and GAPS (an elimination diet focusing on gut health).

“New Year, New You”: An Origin Story

Nobody seems to know exactly when it first entered the zeitgeist, but they’ve got theories.

“I don’t know the origin of ‘new year, new you,’ but it does strike me as an opportunistic time for diet companies, who have picked up on cultural shifts and changed their messaging to not be diet companies. It’s a time when people are thinking of the things they would like to change in the new year. A natural normal time to reflect on how the past year has gone. For [companies], an opportune time to market their program.”

“The word January comes from Janus, the Greek god of endings and beginnings. This god is depicted with two faces: one looking in the past, and one toward the future. The very name of the month conveys this concept of starting over, starting afresh, casting off the past to turn a new face to the year ahead. Add to this a catchy phrase like ‘New Year, New You’—which was most likely conceived by a magazine copywriter—and you can see why it has become one of the most overused phrases in January.

“The problem with the entire ‘New Year, New You’ concept is puts incredible pressure on an individual to start now!—and implies that the ‘old you’ needs to be overhauled, that something is wrong with that ‘version’ of you. Nothing could be further from the truth. One of the best New Year’s resolutions one can make is to express gratitude every day for the things we do have and do love about ourselves. But as a former editor-in-chief of Shape, I know that ‘Be Grateful This Year: How to Get Started Today’ unfortunately doesn’t have the same ring or sales numbers as ‘New Year, New You: Drop 30 Pounds Starting Today!’ The world of marketing and profits is dictating how people feel about themselves and their bodies. And that is not what Janus was ever meant to symbolize.”

“I think you’re right to look at the timeline for when dieting for weight loss became a mass phenomenon to begin with, and the more that we came to see higher-than-average weights as not a result of natural variation and a normal part of life, but as a moral failing. It makes sense it might graft onto that with a [New Year’s message of], You can make changes that somehow you can’t make at any other time of the year or somehow will have the desired effect this year vs last year. The reality is, the idea that you’re becoming a new person or completely changing how you look actually keeps people from sustaining [healthy changes].”

“I really don’t know the first usage, but I recall seeing it even in old magazines from the ’50s, if not before.”

“I would imagine that it came from the promise of a new year where you turn the page on the past and magically start anew. This is usually not an achievable goal. People seldom keep their resolutions. The New Year is seen as a new beginning, a time to change what might be…unchangeable. That’s where self acceptance comes in, where you acknowledge the difficulties of changing your attitudes and behaviors and focus on what small steps may be achievable, and build on those.”

“I still remember the first time I saw it… It was 2002 (ish) and I was working for a start-up health website that was just starting to dabble in email campaigns and newsletters. One of my editors submitted an email for editing with the subject ‘New Year, New You’ to promote our latest offering: an online diet and wellness program. I loved it! It was clever and short, evocative and empowering! We’d get great open rates and click-thru rates. It was perfect!”

*This quote appeared in a BPD Advertising blog titled “New Year, Same Old Headline!” on December 17, 2015.

With so many new “fixes” promising a “new you”—and so much money being thrown about to ensure you see those promises, with weight loss and fitness companies spending about four times as much on advertising at the beginning of the year than other times (Noom spent $21 million on Facebook ads alone last January)—it’s no wonder that millions of Americans make (or more accurately, remake) the commitment to lose weight minutes after the ball drops.

How a Diet Becomes an Eating Disorder

Let’s be clear: All diets aren’t inherently bad. In fact, a 2022 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found that “intention to restrict food intake and actual restriction of dietary intake are both safe and effective for weight management and promotion of good physical and mental health in those without significant risks for the development of eating disorders.”

The study authors even theorize that “weight-loss interventions that promote healthy weight loss but not negative attitudes toward one’s body might result in both weight loss and reductions in eating disorder symptoms and presumably risk of developing eating disorders.”

This, of course, remains to be proven—and food restriction in those with EDs come with a cluster of concerning physical effects.

Sarah-Ashley Robbins, M.D., is a family medicine doctor at the Gaudiani Clinic, which gives medical care for people with eating disorders. Among the health problems she commonly sees with anorexia or restrictive eating disorder are osteoporosis (which she regularly diagnoses in teenagers and people in their 20s), low-resting heart rate (the body’s way of preserving energy), chronic coldness, constant tiredness, and frequent gastrointestinal issues. Additionally, people who menstruate can lose their period.

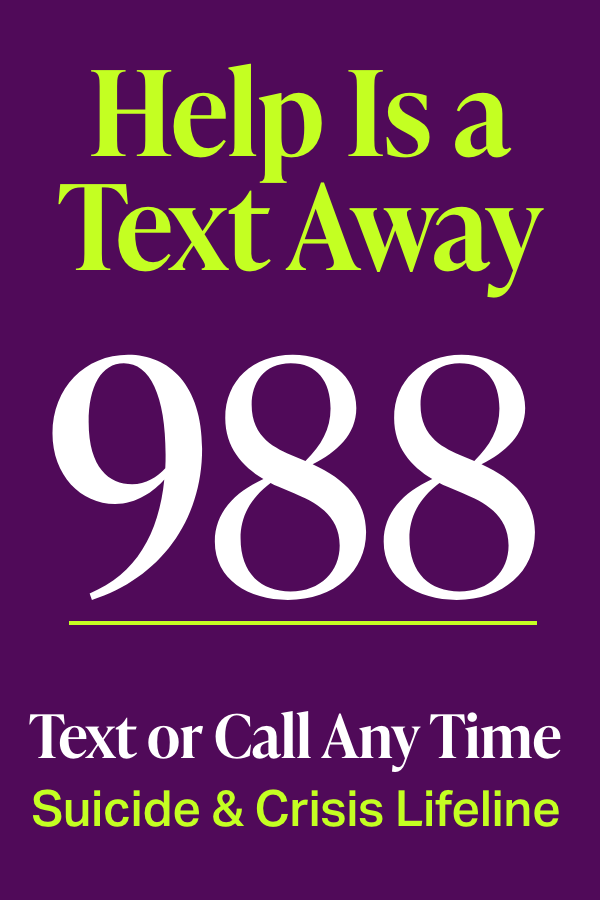

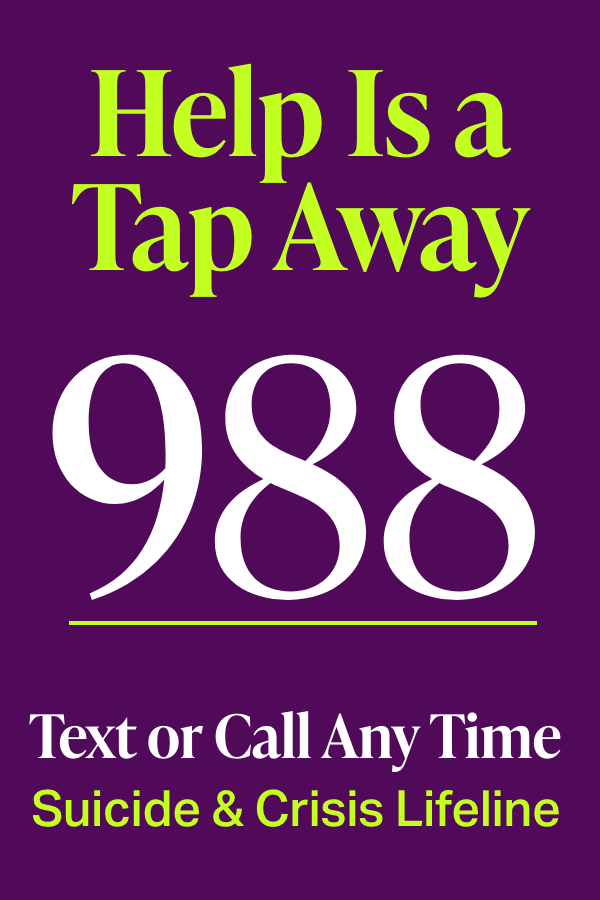

Most seriously, eating disorders are linked to death, both because the body breaks down and because the person can, too, leading to suicide. According to the Eating Disorder Coalition, one person dies every hour as a direct result from an eating disorder. Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness.

The stats are alarming. Per a 2019 study published in BMC Medicine, people with lifetime eating disorders are five to six times more likely to attempt suicide than those without an ED. (The highest rate was found in those with a subtype of anorexia that involves binging and purging.) According to another study, a third to a fourth of people with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa have attempted suicide. And, when compared to others of their same gender and ages, those with anorexia are 18 times more likely to die by suicide; those with bulimia, seven times more likely.

A June 2020 report from Deloitte, AED (Academy for Eating Disorders), and STRIPED (Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders) found that around 20 percent of people who experience anorexia nervosa die by suicide.

Eating disorders, as we know, are caused by a complex mix of genes and environmental factors. Dieting alone doesn’t cause an ED, but it can push people who already have body image or eating issues into worrisome patterns. “Not all people that diet go on to have an eating disorder,” says Natalie Boero, Ph.D., associate professor in the department of sociology at San Jose State University, “but most EDs started with a diet.”

Danielle Catton, a 35-year-old digital content creator in Ontario with a history of disordered eating, can hardly remember a time when she wasn’t on a diet. “I was 11 or 12 on a camping trip and eating only salad because I felt like I had to lose weight,” she says. When that didn’t work, she started the Atkins diet at age 13.

Her desire to lose weight morphed into an eating disorder by high school, when she had aspirations of being on Canadian Idol and felt she had to be skinny to succeed as a singer. “Every January 1 it was like, Okay, I’m going to do this. I’m going to start this diet and lose weight,” she says. “I’d start excessively exercising and restricting my diet. Everyone else was doing it, too, so it was normalized.”

But dieting wasn’t getting the job done, so she started binging and purging to lose weight, receiving positive attention—including from boys for the first time—which fueled her disordered eating behavior.

Catton is hardly the only one for whom dieting isn’t effective. A 2020 study published in BMJ looked at more than 21,000 people on 14 “named” diets and found that the Atkins diet—the one Catton tried at age 13— resulted in the highest weight loss, of 12 pounds. But a year later, the weight loss and improvement in cardiovascular risk from all the diets was, essentially, gone.

In other stats from Berkeley, 65 percent of dieters return to their pre-diet weight within three years, and only 5 percent of people who drop pounds on a restrictive diet (such as those that cut out foods and categories) keep them off. In fact, one of the leading obstacles as to why people don’t stick to diet resolutions, per Statista, is “the changes are very restrictive” and, further down on the list but not insignificant, “The changes are consuming my thoughts.”

Clinical psychologist Chantal Gil, Psy.D, who has extensively studied behavioral science, says that being set up for failure in this way can be especially damaging to mental health, particularly for people with disordered eating. Ultimately, this cycle of unrealistic goal setting, and the failure that follows, takes an emotional toll. “For anyone, the feeling of failure is really demoralizing and terrible,” Dr. Gil says. “And this is [amplified] for people who are perfectionists, which we often see in our population of folks with an eating disorder.”

Catton, now in therapy and recovered from her eating disorder, still has moments of temptation to binge and purge again. Just last January, one line from a weight-loss-plan’s commercial stuck in her mind: “This is the year I’m going to do it!” a celebrity cheerfully exclaimed. “It was triggering to me,” Catton says, “because that is the thought process that a lot of people dealing with disordered eating have.” January remains difficult for her.

As it does for so many others who have an active ED or are in recovery. It’s why conversations with patients often change around the holidays and through January, says Dr. Gil, an eating disorder specialist at the Duke Center for Eating Disorders. “A lot of anxieties come up as we approach the time of year where there’s all these big meals happening—it’s so food-focused.” This, she adds, bolsters the feeling that you need to restrict food, which often extends to January’s end.

And despite what companies might tell you, restricting food in some way is at the heart of most weight management programs—a market that hit $132.7 billion in 2021 and is expected to grow another 9.7 percent by 2030. Meanwhile, the rate of eating disorders is also up. According to a study in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the prevalence of eating disorders increased from 3.5 percent of the population between 2000 to 2006 to 7.8 percent from 2013 to 2018.

Although the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD) estimates that 28.8 million Americans, or 9 percent of the population, will have an eating disorder in their lifetime, that number is likely far higher. A 2022 study published in The Lancet Psychiatry found that there were 41.9 million additional, previously unreported cases of eating disorders in 2019, four times as high as previously noted.

Earlier data, it turns out, hadn’t included binge-eating disorder and OSFED (Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder). By way of comparison, the number of people with EDs is now similar to those with drug-use disorders and more common than bipolar disorder and autism spectrum disorders.

This highlights a truth that the general public, and even certain medical practitioners, don’t realize: Eating disorders aren’t an issue for only the very gaunt. In fact, less than 6 percent of people with eating disorders are medically diagnosed as “underweight.”

The Clumsy Connection Between Weight and Health

“New Year, New You” is like its own little fake news factory, promoting myths it can take centuries to unknot. So let’s get this straight: A thinner “new you” does not necessarily mean a healthier you. “Bodies can be healthy at different sizes—thinness is absolutely not a metric for health,” says Dr Robbins.

Studies regularly use Body Mass Index (BMI) as a way to show correlations between health issues and weight. But there are countless studies showing BMI is an inadequate measure for health. First, it’s a poor indicator of body fat percentage, says Dr. Robbins. It doesn’t show the differences between muscle and fat, which means it can’t accurately predict one’s risk for health problems. And it doesn’t account for the wide range of racial and cultural backgrounds—this is why some consider it racist.

So why is it still in use? “BMI is a blunt object that tells us nothing about health. But with 300 million people, sometimes you need some blunt objects,” says Dr. Boero. Unfortunately, this bluntness leaves out all nuance.

Most people, including many physicians, don’t understand that not all fat is unhealthy, says endocrinologist Elena A Christofides, M.D., who sees patients who have eating disorders and works with people to both gain and lose weight healthily. What’s concerning is adiposity, or an excess of unhealthy fat found in certain areas of the body.

Neither BMI nor eyeballing a person can tell you whether “the fat they’re carrying is unhealthy fat, or that their weight is unhealthy because of size,” says Dr. Christofides, CEO of Endocrinology Associates and managing partner of Medizen, a medical wellness and aesthetics center in Columbus, Ohio. “Is the fat located in places that are healthy or unhealthy? It’s also the combination between your adiposity and your genetics and lifestyle.”

Dr. Boero is as blunt as BMI in describing the fat bias within the medical community. “We prescribe for fat people what we call a disorder in thin people,” she says. “If you look at what many people who struggle with anorexia do—constant weighing, cutting out entire food groups, cutting calories, exercising to cancel out calories, keeping food logs,” she explains, “it’s similar to what we recommend to treat obesity.”

The judgment stems from both ignorance and bias. “Most of the medical profession is fairly uneducated about obesity,” says Dr. Christofides. “They have the same societal biases that you’ve failed as a human being, but also have the bias that the minute you have excess adiposity that you will have these problems and you brought it on yourself. And neither is acceptable. So patients don’t have support from either the medical profession or society, and then it gets worse in the new year.”

“There are a million studies about how horribly fat people are treated by medical professionals,” adds Dr. Boero, speaking from both personal and professional experience. “You go in with a hangnail, and they tell you you need to lose weight. I’ve been hearing that one for 25 to 30 years.”

What these studies also show is that larger patients respond to this judgment and shame by avoiding medical appointments entirely or coming in later than they should, which leads to worse health outcomes. As Dr. Boero puts it: “Often, things are diagnosed later.” Things that, then, get correlated not with a late diagnosis, but with being overweight.

“There’s no health problem experienced by fat people that’s not experienced by thin people,” says Dr. Boero. “There may be some things that are more common among larger people, but weight can become a masking variable for things like activity level, genetics, poverty, racism, and medical bias.”

The latter? It even appears in public health messaging. One study found that 44 percent of obesity-related public health campaigns included a “stigmatizing strategy,” despite the fact that “research shows people evaluate messages as more helpful and motivating when they are not stigmatizing—or weight-based at all—but rather focus solely on healthy behaviors.”

Indeed, studies testify that weight stigma can actually make binge eating worse. “The way we talk about fatness, the way that we completely hinge everything from beauty to morality to work ethic to human value on body size and appearance, absolutely can encourage and further deepen eating disorders and eating disorder behavior,” says Dr. Boero.

Stigma is so sinister, it can also prevent people from getting help when they need it. You might assume that January and February are busy months for eating disorder docs. Not so, says Dr. Gil. “Generally, this is because people have so much shame about how the holidays went, and the messaging around New Year’s and dieting contributes to that shame,” she says. “It actually pushes people away from getting the support they need because they’re feeling down on themselves and they don’t want to show up when they’re in a bad place, even though that’s what we actually encourage.”

None of this is to say there aren’t legit health issues associated with excess adiposity. But the links are often more correlational than causational. “Increased BMI is correlated with diseases associated with adiposity,” clarifies Dr. Christofides. “We say adiposity-based chronic disease. It is not adiposity-caused.” Type 2 diabetes, for example, is correlated with increased adiposity, but someone may not look overweight because of where they hold their weight, she explains.

But again, BMI—which anyone can learn on their own with an online BMI calculator—can only tell you so much. It requires lab tests to determine metabolic markers like cholesterol and triglycerides. Even then, says Dr. Robbins, “Health is not defined by a set of numbers or measurements. It’s determined by looking at a person’s life and how they are able to function in the world.”

Dieting: World’s Most Effective Weight-Gain Strategy?

Once a dieter, always a dieter. So says British research, which found that the average dieter tries 126 different eating plans throughout their lifetime—that’s basically two new diets a year throughout their adult lives.

This type of chronic dieting is also known as yo-yo dieting, and many believe its side effects are worse than those of being obese. Particularly for those with an ED or a predisposition for one.

Which means: Dieting itself is practically a chronic condition.

Chronic yo-yo dieting, a form of disordered eating, puts stress on the heart, says Dr. Robbins, which increases the risk of heart disease and premature death. Plus, per the 2016 Journal of Food Research literature review, yo-yo dieting can lead to “food obsession, constant calorie counting, distractibility, increased emotional responsiveness, and fatigue.” Additionally, as the study authors wrote, “chronic dieters also tend to overeat, have low self-esteem, as well as suffer from some eating disorders and depression.”

And then there’s this: Yo-yo dieting often leads to weight gain.

“It’s such a conundrum, because you’re told you’re unhealthy, so you keep trying to lose the weight, but it always comes back on and it’s this weird never-ending cycle,” says Mental contributor Devash. “Doing all this work to wind up where you started—unhealthy but apparently even unhealthier than before and more likely to gain weight.”

Which is worse, the health issues associated with weight or yo-yo dieting in an attempt to lose that weight? You can make the case either way and “that’s kind of the problem,” says Dr. Christofides. “The way it’s portrayed depends on who you’re trying to convince.”

When she was younger, Dr. Christofides herself “was a victim of the same social mentality. I did every crash diet. You name it, I did it.” One gave her kidney stones. Another, gallbladder disease. “Yo-yo dieting is bad because of the things people do out of an attempt to change their BMI without thinking about the consequences, because they view the short-term consequences as being reasonable and acceptable risks,” she says. “And because they are worried about the long-term consequences of BMI.”

But improving health outcomes in obese people is far less cut-and-dry than “lose weight” or “go on a diet,” Dr. Boero says. “We know it doesn’t work to make fat people thin.”

There’s plenty of evidence, however, that we can make people healthier no matter their size, she says. Of course, it’s complex, including relief from stigma, access to good medical care, not living in poverty, not experiencing racism and sexism, and equal food distribution. “And Congress just voted down extending universal school lunches,” Dr. Boero opines.

We Can Do Better

“The American dream translated to the American body: Work hard,” says sociologist Natalie Boero, Ph.D. “It’s like saying, Stay in school, kids. But in your shitty underfunded school that’s violent, what are your chances?” With bodies and diets and stigma, let’s all do our part.The biggest reason companies continue to push weight loss messaging: It works (the messaging, that is). “As a society, we don’t like complexity,” says Dr. Boero, associate professor in the department of sociology at San Jose State University. “Complexity that doesn’t sell. And in a culture that’s so highly visual, people want quick answers.”

And unfortunately, the reasons people gain weight aren’t always simple. “The problem with the word obesity is everyone thinks they know what it means,” says Elena A. Christofides, M.D., an endocrinologist in Columbus, Ohio. “But it isn’t what they think it means. Excess adiposity is a disease, and you see actual professionals when you have actual disease. New year’s messaging suggests you can show up at any gym and magically cure your disease.”

Unfortunatley, people often show up to those gyms or start diets in January out of shame and punishment, which studies prove typically backfires. But Emily Dhurandhar, Ph.D., interim associate editor for the International Journal of Obesity, believes we can change this. “As we see with other health conditions, it’s possible to motivate people to seek help and purchase products and services from a place of self-care and self-love,” she says, “from the desire to live life to its fullest, and empowering people to solve the problems ailing them.”

Of course, unlike many other conditions, weight loss is handled differently because of the biases—perpetuated by brands, media, and society in general—that we all hold onto and internalize. Always keep your guard up for weight loss wolves in sheep’s clothing; lifestyle positioning can’t make bad products and services less triggering for you.

“We have a responsibility to educate ourselves beyond a simplistic and biased understanding,” says Dr. Dhurander, chief scientific officer at Obthera, which provides software and services for “evidence-based, personalized obesity management.” “Just as you would educate yourself about cancer and the experience of having cancer before writing about it to do so well and sensitively, the same care needs to be taken when writing about weight loss.”

Ketchum, a global PR agency, recently took steps to do just that. Jaime Schwartz Cohen, R.D., Ketchum’s SVP, director of nutrition, hosted an expert panel for her team about the dangers of “New Year, New You” messaging. They’ll use the panel gleanings, she says, to make clients “more aware that ‘New Year, New You’ is an outdated media moment” and “that research shows tying health outcomes to weight loss and general betterment is ineffective and can be harmful, eliciting feelings of failure and shame.”

What works better, according to the panel’s psychology experts? Building on habits you already have (called habit stacking), and flipping the narrative “to one of positivity and excitement, not coming from a position of fear of disappointment or failure as is seen often in ‘New Year, New You’ campaigns,” Schwartz says. Ketchum will also be advising clients to “focus on what is achievable and simple, versus aspirational,” and suggesting “empowering, not discouraging” images. The Obesity Action Coalition (OAC) offers free photography through its Bias-Free Image Gallery.

“The way we train doctors, nurses, and dietitians needs to shift,” says Katherine Metzelaar, R.D., who believes we need to clear up misconceptions and skepticism around Healthy At Every Size (HAES) practitioners. “We have evidence that we can improve health outcomes without changing body weight and size.”

Social determinants impact our health and wellbeing significantly. “But that makes it messy,” says Metzelaar, cofounder and CEO of Brave Space Nutrition, which specializes in helping people struggling with disordered eating. “It’s much easier to say it’s what you’re eating or because you’re not moving enough.”

Likewise, Dr. Boero believes we must look beyond first-thought fixes. “When I did research on bariatric surgery, [it was like] swapping one set of health issues for another. We’re not asking the right questions,” she says. For example, “I’d like to see more international studies on what is happening in other countries where weight cycling [is less prevalent].”

It’s critical we expand our education of EDs, too. “We as a culture have a really difficult time identifying what an ED is,” she says. “There’s not a lot of training in the medical field. They often don’t have an awareness and there is a ton of weight bias, and yet doctors are making decisions about EDs when they don’t have a clue.”

At Brave Space Nutrition, Metzelaar targets behaviors, not body size—daily movement to improve cardiovascular health, for example, or looking at whether a person with diabetes is eating enough and consistently. Are they getting fiber? “We focus on what’s helpful for certain disease states,” she says.

We need to first acknowledge, then challenge, our own biases. “The way we talk about fatness, the way that we completely hinge everything from beauty to morality to work ethic to human value on body size and appearance, absolutely can encourage and further deepen eating disorders and eating disorder behavior,” says Dr. Boero.

Remember what your 5th grade teacher said about assuming? Yeah, well, it applies to bodies, too. Looking at someone tells you very little about someone’s health or situation. The person who can eat anything, for example, isn’t necessarily more cardiovascularly healthy, says Dr. Boero.

She herself has experienced the opposite bias. An avid exerciser, Dr. Boero sees new people at the gym this time of year who don’t recognize her. “I’m the fat woman, and I’ll be lifting weights, and someone will inevitably come up to me and say, You go girl. Meanwhile, I’ve been doing this several days a week for the past 25 years!” she says. “I know people mean well, but no wonder we don’t want to go to the gym.” As a professor who teaches research methods, she encourages people to go where the data takes them. “Some people shield themselves from other information,” she says. (Don’t be those people.)

Both obesity and eating disorders are extremely complex, stemming from a blend of genetics, environment, lifestyle, and, sometimes, inequity. But there’s a tendency to blame the person alone, when many contributing factors are out of their control. Here are a few you may not have considered:

- Your access to physical activity. “I am the world’s biggest proponent of physical activity,” says Dr. Boero, “but what do you need for physical activity? You need leisure time. A safe neighborhood. And moreover, we’ll make sure you don’t have the time and space to do any of that.”

- Your school. “Think about how many people of all sizes have trauma in PE classes,” Dr. Boero says. “We set people up so early in life for exercise, then we wield it as a punishment.” Metzelaar has clients who were put on diets at their schools, forced to track calories or cut out certain foods. “While it’s usually not intentional, a lot of harm is caused in the school system,” she says. One study within New York City schools found that teens who were given an “overweight” label on their BMI report card had significantly higher BMIs the next year compared with a non-labeled control group.

- Your parents. As Metzaleer explains, people’s disordered behavior with food or their body doesn’t start in adulthood. When you’re a kid, you don’t have much control over, well, much. “When difficult things happen, when we don’t have adults who can emotionally regulate, we go to the things that are more accessible, and what tends to be most accessible are food and one’s body,” she says. “In particular with food behaviors, [control] gives a temporary sense of relief or soothing from a nervous-system perspective. We feel like things are ok while we’re doing it.” EDs, she says, arise as a way to cope with difficult things in life.

Finally, if you’re on TikTok, it’s helpful to follow people with a diversity of bodies. “Research around TikTok shows the algorithm is able to give you what you’re looking for,” says Metzaleer. “If we’re shown the same bodies over and over, we start to believe that’s the way we should look, even though a small percentage of the population looks that way.”

“I don’t think we’re trying to do what we say we’re trying to do [in making people healthier],” she goes on. “I think we’re trying to individualize the marginalization of large swathes of society, and there is a multibillion-dollar industry out there profiting from that.”

When Weight Loss Hides in the Shadow of Wellness

When researching her book, Killer Fat: Media, Medicine and Morals in the American Obesity Epidemic, Dr. Boero uncovered what she calls “the masking phenomenon of health.” She believes that, because as a society it’s often considered “vain, shallow, or not feminist” to care about looks, health becomes “a secondary or masking phenomenon” for things like weight loss.

The codewords are starting to show up everywhere. A YouGov poll, for example, found that of the 37 percent of Americans who are making 2023 resolutions, the top one (at 20 percent) is improving physical health. Coming in at #3, #4, and #6: exercising more, eating healthier, losing weight. Isn’t this all pretty much weight loss in disguise?

Dr. Anderson believes, as New Year’s resolutions go, “health” can indeed be a euphemism for “dieting.” If you sort by gender the YouGov poll participants who put physical health at the top of their resolutions, women were more likely to list those weight-related goals: eating healthier (23 percent), exercising more (23 percent), and losing weight (21 percent).

“My hatred of ‘New Year, New You’ messaging around weight and health is that it only reinforces, among literally every human on the planet, that your weight is a result of you not going to the gym more regularly,” says Dr. Christofides.

“In a culture that worships thinness, where we’re told that we can achieve anything and everything that we want as long as we’re in a thin body,” says Katherine Metzelaar, R.D., cofounder and CEO of Brave Space Nutrition, which specializes in helping people struggling with disordered eating. It’s tricky for people to put their true intentions into words, she says. When someone tells her they want to “eat healthier and exercise more,” her immediate questions are: What are the things that are contributing to this desire? What do you hope to feel or experience by doing this? How do you define “healthy eating?”

Diet companies have picked up on this type of sentiment, says Dr. Boero, shifting their marketing to focus on health and wellness. “Even when fundamentally the plan hasn’t changed that much, health is absorbed as a way to pitch it,” she says.

Though sometimes well-intentioned, this can be dangerous for those with a history of disordered eating. “Dieting doesn’t have a capital D anymore. Now it’s, Oh no, we’re a lifestyle program or a wellness culture, which makes it sneaky and especially difficult for people in ED recovery, because it’s harder to spot,” says Metzelaar.

In fact, one reason some of her ED patients don’t visit in January is because they’ve fallen for such marketing. “They’ve engaged in some type of program that promises them it isn’t a diet,” she says. “But they get to a point where said program sends them back into disordered eating cycles.”

If this sounds familiar, it’s because there’s a pretty decent chance you’ve heard at least half a dozen people tell you that they’re cutting out sugar, carbs, or doing Whole30 in the name of health. “There has been this shift to ‘detoxing,’ and removing ‘bad’ things,” says Dr. Anderson. “So now foods have been given moral qualities: Some foods are ‘good’ and some are ‘bad.’” This thinking, she explains, has led to the rise of orthorexia, or an obsession with healthy eating.

It’s something Hannah Belvo, a 29-year-old emergency room technician, can relate to. “Growing up, every January, my dad always set health-related resolutions and he would want my sister and I to do,” she says. “So every year I would think about what goals I could set to change my entire body by the end of the year.” Often, this involved excessively working out and restricting food.

The behavior continued in college, where Hannah played softball and wanted to be the best athlete she could. “I was working out a lot, which my teammates motivated me to do, and I started losing weight. I wasn’t ever overweight, but I liked the changes I was seeing in my body and it [morphed] into an obsession,” she says. The immense stress of college piled on. “The one thing I could control was my eating, and it slowly started taking over my entire life.”

The type of January weight loss pressure Belvo experienced doesn’t affect only those with a clinical eating disorder diagnosis. “Unfortunately, many people struggle to some degree at some point in their lives with their relationship with food or body image,” says psychologist Rachel Goldman, Ph.D., clinical assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. who focuses on health behavior change, disordered eating, and eating behaviors.

Whether you have a history of disordered eating or not, “New Year’s resolutions surrounding weight loss send the message that we have to change, and that something isn’t right,” she says. “It’s damaging regardless of someone’s eating behaviors, body image, or self-confidence.”

But why do we keep coming back to dieting when we know it’s not sustainable? Dr. Goldman believes it’s the lure of the quick fix. Dr. Gil agrees, adding that, coupled with powerful advertisements—often including people or celebrities we can relate to—it’s hard to resist.

To be fair, there are plenty of people pushing back on the idea that a thin body is an ideal one and celebrating bodies of all shapes, sizes, and abilities. And yet, despite a decade of body acceptance in the mainstream zeitgeist, rates of eating disorders not only haven’t slowed, they’ve increased. One theory? The larger bodies now being shown as beautiful have a certain look to them, says Dr. Anderson—one that can be just as hard to achieve as a thin silhouette.

Social media doesn’t get a pass here, either. Recent research from the Wall Street Journal found that TikTok pushes thousands of how-to videos about getting by while eating only 300 calories a day and hiding disordered eating behavior from others.

The Social Media Comparison Trap, Going Strong

In the early aughts, women’s narrow beauty views were often blamed on TV and magazine images. Per a 2004 study, 69 percent of teen girls said that magazine photos of thin women influenced their version of an “ideal” body, and a 2007 study linked increased consumption of articles about weight loss and diets with a higher likelihood of engaging in unhealthy eating behaviors. Yet another study, in a 2005 issue of Body Image, found an increase in body dissatisfaction in many college women after they watched “thin and beautiful” images in mini movie clips.

But if magazines were a megaphone for anti-obesity messages, social media is an IV straight to the brain. There are 1.2 million Instagram posts using #newyearnewyou, 107.3 million TikTok views of the hashtag, and 1.5 billion Tok views of #newyearnewme. “Before, people used to idolize celebrities in magazines and on TV, which led to unhealthy behaviors,” says Dr. Goldman. “But now we’re bombarded even more because of social media. And it’s not just celebrities people are comparing themselves to now, but influencers too.”

One problem with wellness influencers, says Kylie Mojaddidi, a 34-year-old content creator who struggled with bulimia in the past, is that the vast majority are women who are thin. It’s not just her opinion: One 2019 study demonstrated that social media heavily promotes the thin-ideal, which can lead to unhealthy behaviors and body dissatisfaction.

“People on social media who are sharing what a day of eating looks like for them or showing their clean eating diet meals can lead to self-comparison—it’s human nature to compare,” Dr. Goldman says. And if you think you aren’t as thin, strong, or fill-in-the-blank as the influencer you’re watching eat a forkful of quinoa, it can make you like crap, she says.

The average person spends two and a half hours a day on social media, time that Dr. Goldman firmly believes is connected to disordered eating behavior. Research supports her. One study identified a strong connection between social media use and healthy eating concerns in young adults.

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Blood Sugar Control

And by funny, we mean scary. Unless you have type 2 diabetes, step away from the prescription drug Ozempic. It can be particularly dangerous if you’ve got an ED.In recent months, the diabetes drug Ozempic has made headlines for its weight loss prowess (despite such side effects as incessant vomiting, diarrhea, and heart rate spikes). On TikTok, the hashtags #Ozempic and #OzempicChallenge have gone viral as people have started using the prescription medication—which is meant to lower blood sugar and A1C in those with type 2 diabetes—to drop pounds.

The drug’s manufacturer says it is not approved for weight loss, but this hasn’t stopped doctors from prescribing it off-label, according to the American Council on Science and Health. So many people have started misusing the drug in this way that it has caused a shortage for people who actually need it.

“I am fundamentally, completely against people who don’t have diabetes using Ozempic,” says Katherine Metzelaar, R.D., cofounder and CEO of Brave Space Nutrition, which specializes in helping people struggling with disordered eating. “One, if someone is using it short-term for weight loss, what’s gonna happen when they stop using it? We don’t have this research, but long-term it could lead to more weight gain, and it could be super dangerous. Why do you need to take a med to make your insulin more sensitive when your insulin is working as it should? This could lead to low blood glucose levels. You could pass out from that.”

“My doctor suggested Ozempic,” says Mental contributor Meirav Devash, who has weight-cycled for years. When told it’s made for people with diabetes, she responds: “That’s funny, because everyone I know who is on it doesn’t have diabetes.” Her doctor only backed off because Ozempic’s vomiting risk is contraindicated with Devash’s bleeding risk from her esophageal varices.

Metzelaar worries that Ozempic could go the route of Fen-Phen, a combination of two Rx drugs, fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine, used to treat obesity in the 1990s; the FDA pulled them from the market in 1997 after their usage was linked with potentially fatal heart valve problems. Ozempic, Metzelaar says, could be extremely dangerous for people with eating disorders.

“Because many doctors don’t have a lot of training of EDs, they will often make assumptions based on someone’s body size as to what kind of eating disorder they have, or they don’t ask, and could just prescribe a medication,” she says. “They wouldn’t know this person in a larger body isn’t eating at all, or this person in a normal body is purging all day. If you don’t get that kind of information, I can see [this drug] causing serious harm especially [if prescribed] for people who have disordered eating, and if in the middle of an ED, they might be really inclined to ask for it.”

As you can imagine—and have possibly experienced first-hand—the twisted thinking that thinness-is-virtuousness is far from mentally healthy. “There’s a misconception that so many people have, which is that to lose weight or to be healthy you have to have really strong willpower or be restrictive,” says Dr. Goldman. This all-or-nothing thinking is exactly what can lead to or encourage disordered eating behaviors.

For example, “someone feels virtuous when they are able to give up sugar,” says Dr. Anderson. This is particularly potent right after the holidays, when many have “indulged”—leading them, by the time January rolls around, to set (you guessed it) “New Year, New You” weight loss goals.

New Year, New Changes—The Good Kind

Yes, we’re still getting email offers from a certain weight-loss company suggesting easier weight loss has finally given us a reason to be happy.

But we’re also seeing slivers of hope that, slowly, things may be moving in a more body-accepting, less ED-triggering direction.

In a Forbes Health/OnePoll survey of 1,005 U.S. adults (yes, there are dozens of resolution polls—take your pick), the top New Year’s resolution was not improved diet, improved fitness, or losing weight. It was improved mental health. “The survey findings,” write the editors at Forbes, “suggest a cultural shift in what Americans value when it comes to wellness, pushing back against the idea that health is measured simply by the number on the scale.”

Likewise, InStyle recently proclaimed: “Less dieting, more therapy.” Even Lands’ End name-checked “New Year, New You,” calling it “a way to make you buy a health club membership,” and instead suggesting you walk around your neighborhood for 20 minutes three times a week for free.

In mid-December, the New York City office of global PR firm Ketchum held an internal panel on the very topic of “why we need to retire the New Year, New You narrative in food and wellness communications.” Hosted by Jaime Schwartz Cohen, R.D., SVP, director of nutrition at Ketchum, the panel brought together psychologist Dr. Goldman, weight bias researcher Dr. Dhurandher, and two dietitians to teach the Ketchum team, as Schwartz says, how to “responsibly and effectively communicate science so that we can help create change.”

And just a week ago, People Editor-in-Chief Wendy Naugle announced that the brand’s two-decades-old annual January “Half Their Size” issue would now be called “Beyond the Scale.” In a December 28 letter, she acknowledged that although previous stories relied on lasting lifestyle changes, not fad diets, “sometimes the takeaway was that the number on the scale was what mattered most. No more.”

As Naugle tells Mental, “We all know when you step on the scale, the number can go up and down, sometimes no matter what you do. If you hitch all your goals to that number, it can set you up for failure.” What People’s transformations will focus on now? What she calls “meaningful wins.”

As an example, Naugle cites Tamara Walcott, a 39-year-old mom who set a world record in weightlifting. Click to the story, and you’ll still see before and after photos and her weight loss in big type. But go beyond the headline, and the vibe is certainly that of holistic triumph.

Pay close attention, and you’ll find that Walcott, minus 140 pounds lost, currently weighs 275. Which begs the question: Would her BMI—knowing all the faults of that outdated measurement tool—put her in an “obese” category, classified as unhealthy when she is, in fact, one of the strongest women in the world, built of pure muscle?

As Dr. Christofides and so many others keep shouting into the void, health isn’t about weight. Or size. It’s the excess adiposity—that unhealthy fat, which shows up in very specific spots—that can cause health problems. Speaking of fat, Walcott herself says she “never called it weight loss—I call it fat loss.”

Today, Mental contributor Devash seems less concerned with what her scale says than those around her do. “How you get treated as a fat person is the worst part of being fat,” she says. “It’s the look that your plane seatmate gives you when your hips touch them because the seats are too small. It’s your friend at brunch looking at your plate of pancakes and saying, You’re not gonna eat all that, are you? It’s my mom harping: It goes right to the hips.”

After a lifetime of disordered eating, in 2023 Devash is taking anti-obesity messaging to task. Starting with doctors who, she says, use lose-weight directives as a catchall. “For the past few years I’ve been responding with, Great advice. But until then, what can I do to improve the situation besides weight loss since that will take a while?” she says. “I’m actually going to stop saying that and amp it up to, Great advice. Now what would you tell a thin person?”

She’ll also be trying to stop losing weight just for the sake of it—and finally end her cycle of weight cycling. “To be honest, lifting weights and eating salad is not my lifestyle,” she says. “I think it’s more important for me to focus on getting in better cardio health and getting stronger than to focus on a number.”

It’s a whole new her, albeit not the kind of before-and-after transformation that lands a person an influencer contract. But times, they are a-changing. Maybe next year.

Check Out The Rest of Our Eating Disorder Coverage

What to Do When New Year’s Weight Messaging Sends You Spiraling

The Mentally Health-iest Ways to Set New Year’s Resolutions (Make That: Intentions)

Geek Out on Our Sources

$71 Billion Dieting Industry: https://www.cnbc.com/video/2021/01/11/how-dieting-became-a-71-billion-industry-from-atkins-and-paleo-to-noom.html

Anti-Obesity Messaging and Eating Disorders: https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Fulltext/2021/09000/Treatment_Outcomes_and_Trajectories_of_Change_in.14.aspx

Shelby Castile, LMFT: https://www.shelbycastile.com/

The OC Shrinks: https://www.orangecountyshrinks.com/

Emily Dhurandhar, Ph.D.: https://twitter.com/emilydhurandhar

Obthera: https://obthera.com/

From Normal to Pathological Dieting: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1098-108X(199511)18:3%3C209::AID-EAT2260180303%3E3.0.CO%3B2-E

Origins of Resolutions: https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/when-did-new-years-resolutions-start

Eileen Anderson, Ed.D.: https://case.edu/medicine/bioethics/about/faculty-staff/eileen-anderson

1947 Resolutions: https://www.almanac.com/history-of-new-years-resolutions

Statista 2023 Poll: https://www.statista.com/chart/29019/most-common-new-years-resolutions-us/

John C. Norcross, Ph.D.: https://www.scranton.edu/faculty/norcross/index.shtml

CDC Dieting Stats: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db389.htm

Top Special Diets: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/cdc-says-more-americans-diets-compared-decade-ago-n1246017

American Women Wanting to Lose Weight: https://news.gallup.com/poll/7264/Personal-Weight-Situation.aspx

Rise in Obesity Rates: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

History of Dieting: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310474556_Fad_Diets_Lifestyle_Promises_and_Health_Challenges

Origins of Dieting: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d420/46557810136fa0764363353cca9efcd10b59.pdf

Victorian Era: https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/victorian-era-timeline

Societal Changes Toward Weight Focus: https://www.livescience.com/18131-women-thin-dieting-history.html

Perceptions of Larger Bodies: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2866597/

Smaller Bust-to-Waist Ratios in Magazines: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00287452

Diet Trends (2): https://www.everydayhealth.com/diet-and-nutrition/diet/us-news-best-diet-plans-mediterranean-dash-more/

Diet Trends (3): https://www.eatingwell.com/article/7939435/best-and-worst-diets-of-2022-us-news-world-report/

Dukan Diet: https://health.usnews.com/best-diet/dukan-diet

GAPS Diet: https://health.usnews.com/best-diet/gaps-diet

Weight Loss/Fitness Industry January Spend: https://www.pathmatics.com/blog/new-year-new-you-advertising-data-insights

Noom Ad Spend in January 2022: https://www.pathmatics.com/blog/noom-spent-more-than-21m-on-u.s.-facebook-ads-more-than-peloton-and-ifit-combined

Dietary Restraint Safe In Those Without EDs: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8745028/

Sarah-Ashley Robbins, M.D.: https://www.gaudianiclinic.com/gaudiani-clinic-blog/2020/12/8/asijgfegjy5lfvmzjr5poe6jsu0p56

Gaudiani Clinic: https://www.gaudianiclinic.com

Osteoporosis and Eating Disorders: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6746661/

Low Resting Heart rate and Eating Disorders: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC503388/

Being Chronically Cold and Eating Disorders: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4381361/

Fatigue and Eating Disorders: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459148/

Gastrointestinal Problems and Eating Disorders: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6950592/

Loss of Menstruation and Eating Disorders: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17497704/

Death and Eating Disorders: https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/addiction/article/eating-disorders-rise-study-finds

Suicide and Eating Disorders: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24364606/

EDs and Suicide Attempts: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-019-1352-3

ED Suicide Rates vs General Population: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28846874/

June 2020 Report on Suicide and Anorexia: https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1267/2020/07/Social-Economic-Cost-of-Eating-Disorders-in-US.pdf

Content Creator Danielle Catton: https://www.instagram.com/danielleisanxious/

BMJ Dieting Study: https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m696

Berkeley Stats: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/Quit_Diet_Now

Reasons For Not Sticking to Diet Resolutions: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1122059/challenges-to-adhere-new-year-s-diet-changes-us/

Chantal Gil, Psy.D.: https://www.dukehealth.org/find-doctors-physicians/chantal-j-gil-psyd

Weight Management Industry Growth: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/weight-management-market

Eating Disorder Rates Up: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/109/5/1402/5480601?login=false

Eating Disorders in a Lifetime: https://anad.org/eating-disorders-statistics/

Eating Disorders Underreported: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(21)00435-1/fulltext

Percentage of “Underweight” People with an ED: https://anad.org/eating-disorders-statistics/

BMI As Poor Predictor of Health: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4890841/

Natalie Boero, Ph.D.: https://www.sjsu.edu/people/natalie.boero/

Elena A. Christofides, M.D.: https://endocrinology-associates.com/about-us/dr-christofides/

Endocrinology Associates: https://endocrinology-associates.com/

Medizen: https://www.medizeninstitute.com

Obesity-Related Public Health Campaigns and Stigma: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8428859/

Obesity Stigma: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2866597/

Yo-Yo Dieting as a Form of Disordered Eating: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/weight-cycling

Yo-Yo Dieting and Heart Health: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4241770/

Yo-Yo Dieting and Negative Health Issues: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310474556_Fad_Diets_Lifestyle_Promises_and_Health_Challenges

Yo-Yo Dieting and Weight Gain: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3759019/

YouGov 2023 Resolutions Poll: https://today.yougov.com/topics/society/articles-reports/2022/12/28/americans-new-years-resolutions-2023-poll

Orthorexia: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6370446/

Rachel Goldman, Ph.D.: https://www.drrachelnyc.com/

Body Positivity Movement: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30831334/

Rate of Eating Disorders Up Despite Body Positive Movement: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/109/5/1402/5480601?login=false

Unhealthy Eating Behaviors on TikTok: https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-tiktok-inundates-teens-with-eating-disorder-videos-11639754848

2004 and 2007 Studies on Body Image: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310474556_Fad_Diets_Lifestyle_Promises_and_Health_Challenges

Body Dissatisfaction After Movie Clips: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18089176/

Content Creator Kylie Mojaddidi: https://www.instagram.com/kyliemojaddidi/

Social Media Promoting Thin Ideal: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6861923/

Time Spent on Social Media: https://www.oberlo.com/statistics/how-much-time-does-the-average-person-spend-on-social-media

Social Media and Eating Concerns in Young Adults: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5003636/

Forbes/One Poll New Year’s Resolutions Survey: https://www.forbes.com/health/mind/new-years-resolutions-survey/

InStyle Quote: https://www.instyle.com/lifestyle/new-years-resolutions-list

Lands’ End Quote: https://www.landsend.com/article/new-year-new-you-nah/

People Change to “Beyond the Scale”: https://people.com/health/peoples-editor-in-chief-wendy-naugle-on-going-beyond-the-scale-to-meaningful-wins/

People Tamara Walcott Story: https://people.com/health/this-mom-broke-world-records-and-lost-140-lbs-beyond-the-scale/

“You Can’t Escape the Onslaught” Sidebar

NIH: https://ors.od.nih.gov/News/Pages/New-Year!-New-You!-Fitness-and-Wellbeing-Challenge.aspx

Walmart: https://www.walmart.com/browse/seasonal/new-year-new-you-deals/1085632_4399818_9465857

Cleveland Clinic: https://health.clevelandclinic.org/new-years-resolutions/

“‘New Year, New You’: An Origin Story” Sidebar

Valerie Latona: https://valerielatona.com

Samir Husni: https://mrmagazine.com/

Nancy Etcoff, Ph.D.: https://mbb.harvard.edu/people/nancy-etcoff

BPD Advertising Blog: https://www.bpdadvertising.com/blog/new-year-same-headline

“Let’s Do Better” Sidebar

New York City BMI Study: https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Fulltext/2021/09000/Treatment_Outcomes_and_Trajectories_of_Change_in.14.aspx

“A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to Blood Sugar Control” Sidebar

Ozempic Headlines: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/22/well/ozempic-diabetes-weight-loss.html

Doctors Prescribing Ozempic Off-Label: https://www.acsh.org/news/2022/11/18/ozempic-goes-way-label-16674

Ozempic Shortage: https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages

Issues with Fen-Phen: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1998/09/980902053528.htm