I’ve had an eating disorder most of my life, and for what feels like decades, I would plunk down cash every time a celebrity magazine declared that X celeb had “lost 40 pounds,” or featured Y celeb “as you’ve never seen her before”—accompanied, of course, by a photo of her “new” body.

I avoid those magazines now because, truthfully, I’m triggered. And no wonder: “Research has demonstrated that the media contributes to the development and maintenance of eating disorders,” concluded one study examining the role of media in eating disorders (ED). “The messages and images that focus on the value of appearances and thinness for females have a significant negative impact on body satisfaction, weight preoccupation, eating patterns, and the emotional well-being of women.”

This study was published in 2004—but unfortunately, it’s all too relevant nearly two decades later. Take, for example, a recent New York Post story that declared, alongside images of protruding celebrity collarbones, that “heroin chic is back,” and that we should say “bye-bye” to booties. As if bodies and booties sell on Amazon, where you can charge a smaller one to your Prime account and slip it over your soul whenever trends change.

Body activists, such as Jameela Jamil of the podcast I Weigh—who has spoken publicly about having an eating disorder—took to social media when the story published. “No. No. We are not going back, and how dare the media give this bullshit any oxygen,” Jamil wrote on Instagram. In an op-ed for Paper a few days later, she expressed her disdain for how ’90s fashion trends have brought with them the return of something insidious: ’90s eating disorder culture.

Diet Culture, Revisited

“Heroin chic” was born in the early ‘90s, when Kate Moss and other gaunt models ruled the runways, magazine photography, and clothing ads. The phrase referred to the models’ emaciated features, a trait associated with serious drug abuse. Both as a physical body type and as jargon, “heroin chic” is not only outrageous, it’s irresponsible.

Indeed, what’s so perilous about these one-liners is how they can overtake your thoughts and kick your real values to the curb. “Having your body reduced to a trend can lead an individual to put a premium on appearance, even when centering image above all else is completely inconsistent with what they genuinely believe is important,” says Lauren Rosen, LMFT, director of The Center for the Obsessive Mind in California, an outpatient treatment center specializing in OCD, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders. “This fixation is what traps individuals in behaviors aimed at shrinking or toning or ‘fixing’ their bodies, even when these behaviors threaten their lives.”

I feel this. I know heroin chic isn’t healthy, but when I saw the Post story, I couldn’t help but think: I wish it were my reality.

Unfortunately, I’m not the only one with this thought. “It is very common for people in eating disorder recovery to revert to idealizing a body type that they know isn’t healthy for them,” says Rosen. “And it’s little surprise they would, given that our culture is collectively infatuated with bodies that look a certain way. Besides, thoughts are an inevitable, if not a sometimes obnoxious part, of having a brain. So of course thoughts like I wish I could look like that pop up.”

Model Charlie Howard, who has talked about having anorexia and bulimia through her teens and twenties, was similarly triggered by the Post story. “Even now, after one of the hardest years of my life personally, there are still elements of my brain that wonder if I make myself sick, will my problems go away,” the founder of Squish Beauty wrote on Instagram. “Like all forms of addiction, eating disorders stick with you for life.”

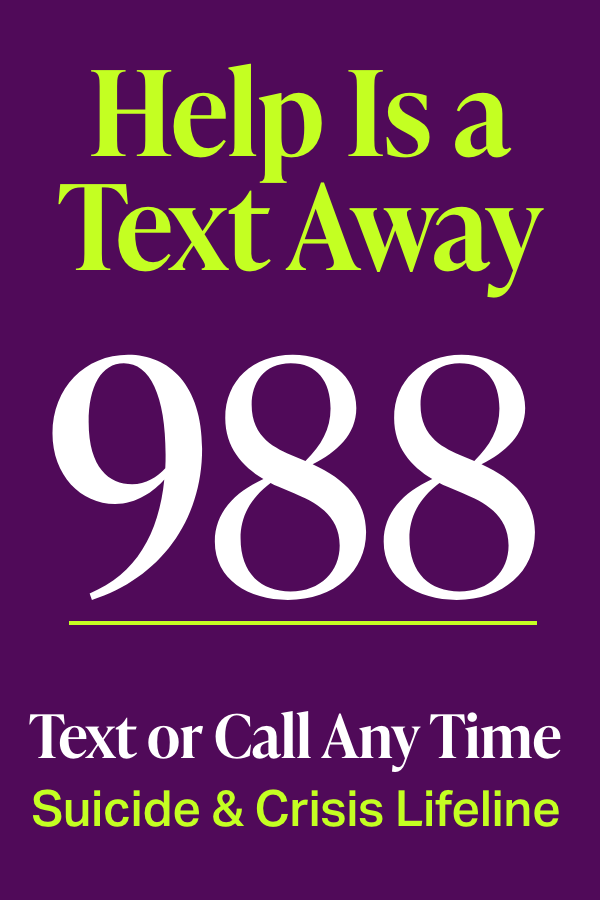

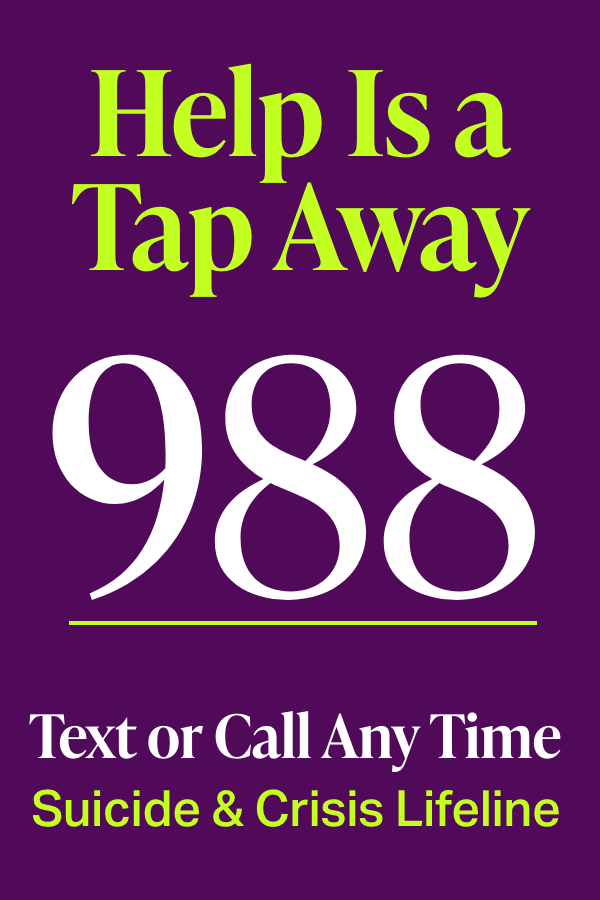

It’s a scary reality shared by too many of us. According to the National Alliance for Eating Disorders, over 29 million Americans experience a clinically significant eating disorder (ED) during their lifetime. EDs have the second highest mortality rate of any mental illness, with nearly 1 person dying every 52 minutes as a direct result of their illness.

When Triggers Arise, Tap Into Your Why

My eating disorder has intensified over the past three years, but what’s also heightened is my awareness. That awareness comes from a decade of working in the beauty and wellness industries and through therapy specifically for my ED recovery, which I’ve only recently taken on in the last year. I’ve come to learn that the amount of brain space my eating disorder takes up is not normal.

I’m thankful, at least, for this awareness. Many people aren’t as conscious of the true damage bodies-as-trends can inflict. Many unsuspecting women read these headlines and feel like there’s something wrong with their bodies.

“The constant shifting of trends keeps us insecure and always trying to achieve something other than what we are,” says content creator and dancer Allison Jacobs, @allison.jacobsss on TikTok, who shares her eating disorder recovery with her followers. “Our bodies deserve better and should be treated with the respect they deserve! Instead, we are constantly trying to alter ourselves to fit into unrealistic and unhealthy perspectives of beauty to feel worthy.”

Clearly, we human beings naturally have drastically different body types. “So the idea of a body ‘trend’ is inherently unattainable for the vast majority of us,” says psychologist Rachel Goldman, Ph.D., clinical assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “When you’re then marketed clothing, food, workouts, and other products by people who have a trendy body type, it can be misleading and promote feelings of failure and shame. It’s important for us to see diverse depictions of health in the media so that it can feel achievable for more people. This requires that we don’t fixate on one body type.”

That body type we fixate on? It also usually happens to be white (and wealthy)—making the very idea of “heroin chic” not just reckless, but privileged, says Akilah Cadet, founder and chief executive officer of Change Cadet, a DEI consulting firm. “It tells curvy women their hips are not to be celebrated or worth seeing,” she says. “As a Black disabled woman, medications, stress from constant pain, or limited mobility determines what I eat and how I can exercise. Heroin chic trends undo the work that has been done for anyone to celebrate their body in any form it is in.”

Eating disorders have classically been seen as a thin-white-girl problem, leaving other communities without the care they need. According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD), doctors are far less likely to ask BIPOC people about eating disorder symptoms, and those in the BIPOC community with EDs are half as likely to be diagnosed or receive treatment—even though Black teenagers, for one, are 50 percent more likely to show bulimic behavior. Women who have physical disabilities also have a higher chance of developing an ED.

GOTTA READ: You Don’t Have to Be Rail-Thin to Have an Eating Disorder

For these and so many other reasons, body manipulation is not something to be discussed lightly, “in a way that makes it sound fun,” says Johanna Kandel, founder and CEO of the National Alliance for Eating Disorders. “A simple, catchy title like ‘heroin chic is back’ can have a significant and detrimental effect on one’s mental health by reinforcing negative beliefs and stigma, such as concepts like one’s external appearance is equated to worth and acceptance.”

It’s important, Kandel says, to move away from this detrimental terminology through an increased repertoire of language used to describe bodies. “We have created more platforms to describe and celebrate bodies in neutral and positive ways that do not place any judgment on them if they are not a certain ‘stereotype,'” Kandel continues. “Bodies are not ‘trends’; bodies are the vessel that keeps us alive and able to do life. Every single body has a unique physiological, genetic composition, with different needs.”

In the moment, if you see a headline and feel triggered, Rosen says one of the most powerful tools is to get in touch with your “why”: What’s most important to you? What do you want to stand for? Who do you want to be? What kind of behaviors will contribute to the kind of world that you want to live in? “Chasing a particular weight and shape can be very seductive because it’s positively reinforced by the world around us,” she explains. “But knowing your why and working toward that aim is far more powerful and fulfilling than any compliment or sense of shallow superiority one might derive from eating disorder behaviors.

“What we’re after is tapping into what matters to you and daring to prioritize that,” she continues. “There is so much that we can’t control in our environment, but we do get to decide how we behave and whether or not that reflects the kind of world that we want to live in. So if you don’t want to live in a world that commodifies bodies, you get to take a stand against this practice by refusing to commodify your own.”

Want more ways to make mental health a priority? Sign up for our newsletter and get Mental in your inbox!

Check Out The Rest of Our Eating Disorder Coverage

New Year, New Eating Disorder: A Mental Special Investigation

What to Do When New Year’s Weight Messaging Sends You Spiraling

The Mentally Health-iest Ways to Set New Year’s Resolutions (Make That: Intentions)

Geek Out on Our Sources

Eating Disorders and Media: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2533817/

Jameela Jamil Eating Disorder: https://www.instagram.com/p/CZ7YIKsv5yL/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Jameela Jamil in Paper: https://www.papermag.com/the-hunger-game-jameela-jamil-2658618118.html

ED Mortality Rate: https://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/what-are-eating-disorders-2/

BIPOC and Disability ED Stats: https://anad.org/eating-disorders-statistics/