Ever felt nervous about an important deadline? Had a case of butterflies before a date? Ding, ding, ding—that’s anxiety. Though it can be uncomfortable, it’s a perfectly healthy (and pretty much unavoidable) experience. But if it starts to disrupt your life, then you may be dealing with something beyond run-of-the-mill unease—an anxiety disorder.

Unfortunately, your fellow Americans are right there with you: Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health conditions in the United States. Approximately 33.7 percent of the population is affected by an anxiety disorder at some point in their lifetime and, research suggests, that number is likely to tick up as younger generations report higher and higher rates of the condition.

And women tend to bear the bigger burden: Between adolescence and age 50, we’re twice as likely as men to have an anxiety disorder. (We’re much more likely to have anxiety and anxiety disorders, actually—lucky us.)

But you don’t have to simply power through, thinking “good vibes only” and hoping for the best (it’s all vibes welcome around these parts): There are a number of effective treatments available. An anxiety disorder doesn’t have to rule your life.

How Everyday Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders Are Different

First of all, know that anxiety in and of itself is a totally normal human emotion—and even serves an important purpose, says Margaret Distler, M.D., Ph.D., a psychiatrist at UCLA Anxiety Disorders Clinic in Los Angeles. “It helps us identify potential threats in our environment to keep ourselves safe.”

Physiologically, it initiates the fight-or-flight response. “Increased heart rate, fast breathing, sweating, chest tightness—all of those things were evolutionarily designed to help protect us in the face of danger,” Dr. Distler explains. Running from a bear is a classic example. A more modern one? The distress you might feel at eyeing your 157 unread email messages.

Cognitively, anxiety also triggers important processes that work a bit like internal HR: vigilance, which helps us assess situations, and planning, which enables us to take action. So, if you’re working on a big project, a healthy dose of anxiety can actually help you anticipate and avoid pitfalls.

Anxiety morphs into a disorder when that physiological response pops up a little too often, a little too intensely, or both. To distinguish between everyday anxiety and an anxiety disorder, a mental health expert may ask three questions.

1. Is anxiety out of proportion to the threat?

If there’s no real threat or you perceive the threat to be much bigger than it really is, that may be an indication of disordered anxiety, Dr. Distler says.

For example, people who are deeply afraid of flying tend to overestimate the risk of getting into a fatal plane crash. In reality, your risk of dying on a scheduled commercial flight is much lower than your risk of dying in a passenger vehicle, bus, or train in the United States, according to the National Safety Council. In fact, the passenger vehicle death rate is 1,623 times higher than the rate for commercial flights. (Do you feel better now? #eep)

2. Is anxiety prolonged?

Anytime you’re in a new or stressful situation, it’s normal to feel anxious. But if the anxiety persists even when the stressor is gone, that may be a red flag. “Usually, we look at a time frame of one to six months to see if someone’s anxiety response is excessive,” Dr. Distler explains.

3. Is anxiety interfering with your life?

This is the most important, illuminating question.

“A typical anxious response is usually adaptive, which means that maybe it’s not a pleasant experience, but someone’s able to utilize those emotions to navigate a difficult situation,” Dr. Distler says.

“But in an anxiety disorder, the anxiety starts to take away from someone’s life,” she adds. “It becomes a hindrance in the ability to make it through the day. Or it gets in the way of the ability to go to school or work, interact with loved ones, or take care of yourself. All of those things are indicators of functional impairment.”

Types of Anxiety Disorders

Meet the (Un)Fabulous Four! Or: the four main types of anxiety disorders. It’s also possible to have more than one.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

“With GAD, you worry about everything,” says Angela Neal-Barnett, Ph.D., director of the Program for Research on Anxiety Disorders Among African Americans at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio. “You’re in a state of highest alert, and it permeates every aspect of your life. You’re always thinking, What if this happens? What if that happens?”

Phobia

Phobia is an anxiety disorder based on fear, so it’s no shocker to learn it’s named after the Greek word for “fear.” As Paul Nestadt, M.D., co-director of the Johns Hopkins Anxiety Disorders Clinic in Baltimore, explains it, “Someone with a phobia has a very strong fear response to something that doesn’t really warrant that type of response.” Common phobias include the fear of needles, flying, confined spaces, or spiders. One Mental reader told us about her ranidaphobia, or fear of frogs—and even has nightmares about them.

Social Anxiety Disorder (a.k.a. Social Phobia)

Social anxiety disorder is characterized by an intense fear of social situations. “This could be talking in front of a crowd, being in settings where you have to talk one-on-one or in groups, or any situation in which you’re subjected to potential evaluation or scrutiny by other people,” Dr. Distler says. As you can imagine, when untreated, this can really crimp your social life and relationships.

Panic Disorder

Anyone can have a panic attack, which is a sudden, overwhelming episode of fear that can be accompanied by a variety of unsettling symptoms. “You may have trouble breathing. Your heart may start beating rapidly. You might go from hot to cold, cold to hot. Your arms and legs may tingle or feel numb,” Dr. Neal-Barnett says. “You might think you’re ‘going crazy,’ having a heart attack, or about to die.”

A one-off panic attack is scary, but it’s not necessarily indicative of a full-blown disorder. Someone with panic disorder typically has recurring panic attacks and often has developed a debilitating fear of having future ones, Dr. Distler explains.

What are Some Symptoms of Anxiety Disorders?

Any of the signs above—constant worry, intense fear, panic attacks—is a good reason to seek expert help. But a tricky thing about anxiety disorders is that symptoms can be wide-ranging, possibly affecting how you think, behave, and feel, emotionally or physically. You may have some symptoms but not all of them, or you you may mistake your symptoms for something else. Here are a few to know.

Hypervigilance and Excessive Planning

Remember the internal HR team you’ve got, vigilance and planning? While they’re part of normal anxiety, too much of either may signal an anxiety disorder, particularly GAD. “Hypervigilance means hyperawareness—when someone is always on the lookout for signs that something could be wrong,” Dr. Distler says. “And if somebody has fears about negative outcomes—my boss is going to fire me, my spouse is going to be angry with me, my loved one is going to die in a car accident—they may plan excessively to avoid worst-case scenarios.”

Avoidance

A hallmark symptom of phobia, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder is avoiding the feared object, Dr. Distler says. Think: going out of your way so you don’t have to drive over bridges, skipping out on dinner parties, or even limiting exercise because you’re afraid it’ll make your heart race, which can feel like a panic attack. Though avoidance can temporarily relieve anxiety, it reinforces the idea that the particular object is dangerous.

Avoidance can also be a sneaky sign of GAD: “Sometimes, people won’t volunteer for projects at work, for example, because they know they won’t be able to handle the anxiety it causes,” Dr. Nestadt explains.

Gut Issues

“People can be very surprised by how pronounced the physical symptoms of anxiety disorders can be,” says Melissa Shepard, M.D., a psychiatrist in Baltimore who’s known for sharing mental health information and anecdotes on TikTok. “We’ll often see people with stomachaches, heartburn, vomiting, or diarrhea who got a full workup at another doctor, but nothing was found to be wrong. Then we’ll treat the anxiety, and the physical symptoms go away.”

GOTTA READ: When Depression Shows Up in Your Toilet

While scientists don’t fully understand the relationship between gastrointestinal problems and anxiety disorders, they know that the gut and brain communicate regularly through the body’s various signaling systems, and each can affect the other, according to a study in the Annals of Gastroenterology. For example, the gut can influence the balance of chemicals in the brain, and the brain can influence movement in the gut.

The gut-brain connection is so strong that digestive and mental health conditions often coexist. In one study, for example, 44 percent of people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) had an anxiety disorder, vs. only 8 percent of people without IBS.

Pain, Fatigue, and Sleep Issues

In addition to GI distress, anxiety disorders can lead to other physical symptoms including muscle tension, headaches, neck pain, restlessness, sleep problems, and fatigue. One reason for this: With anxiety disorders, your autonomic nervous system is often out of balance. The part that controls the fight-or-flight response to perceived danger (sympathetic system) is essentially in overdrive. Meanwhile, its counterpart that manages the rest-and-digest response once the danger has passed (parasympathetic system) is inhibited. In other words, it can’t send the message, Hey, body, the threat is over—you can relax now. Instead, your body stays on high alert, and you may feel the effects of that.

Difficulty Concentrating

“It can be surprising how much anxiety can interfere with your brain’s ability to function, such as problems with concentration or memory,” Dr. Shepard says. Many people describe it as their “mind going blank.”

Though it’s a common symptom, the science behind it isn’t clear. In a group of 175 adults with GAD, almost 90 percent reported problems with concentration, and more severe concentration difficulties were associated with more severe GAD, according to a study in the Journal of Anxiety Disorders. The researchers theorized that worry makes it difficult to concentrate, which can interfere with daily tasks as well as lead to emotional distress.

Irritability

If someone you trust has commented that you seem more irritable lately, don’t dismiss it. Irritability is an underappreciated symptom of an anxiety disorder, Dr. Nestadt says. What gives? “When someone’s anxiety levels are very high, they may not have the emotional reserve to deal with much, so they might snap at people, get angry too easily, or just not have the tolerance for minor annoyances,” he explains.

How Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders Feel, According to Women Who Have Them

“Before presentations in school, I would throw up and be physically ill. I had a lot of physical symptoms growing up that led me to the doctor a lot, but they never really found anything. I’d vomit before dates and job interviews and thought, ‘Oh, it’s just nerves.’” —Stefania Rossi, 25, mental health advocate

“At night, I would wake up frozen in fear, but I’d fall back asleep. But then I’d wake up the next day with a feeling like something’s lodged in my throat that I couldn’t get out. It was awful.” —Haley Weaver, 29, artist

“Everything seems like a risk to me. When I was pregnant with my first child, I would get really nervous: Is my baby moving? And when my child was older and going to take her first shower, I remember saying, ‘Don’t turn the water on really hot because it could burn you and you could end up in the hospital.’” —Kendra Walker, 41, graphic designer

Why Do I Have This? What Causes Anxiety Disorders?

The simplest answer: It’s complicated. But a combination of genetic and environmental factors—that is, anything beyond genetics—contribute to your risk of developing an anxiety disorder.

Genetics

If your mom and dad both have blue eyes, they more than likely passed them on to you. Same with an anxiety disorder? While it’s true that people who are anxious are more likely to have anxious children, “it’s not like you have a dominant trait and a recessive trait, like the way some things in our genetics work,” Dr. Distler says. “We have many, many, many genes that each have small effects, and we’re only now starting to understand them in terms of developing anxiety disorders.”

Research has shown that if your parent, sibling, or child has an anxiety disorder, you’re four to six times more likely to develop the same disorder, compared with the average person. Generally, you’re also more likely to develop any type of anxiety disorder.

Parenting Style

Anxious parents can bequeath more than their genes: We’re talking learned behaviors. “Anxious parents probably raise a child to be more cautious, and the messaging tends to be, ‘Let’s avoid danger,’” Dr. Distler says. “I don’t think of that as a good or bad parenting style. It’s just a style. But in the right genetic context, that type of parenting style may contribute to a child having a more anxious response.”

Childhood Trauma

Abuse or neglect, exposure to violence, growing up in a family with substance use: People who experience childhood trauma are more likely to have any mental health condition, including anxiety disorders, Dr. Distler says. Increasingly, research is revealing that these traumatic events can lead to prolonged, “toxic stress” that can alter brain development and even how genes are expressed.

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

For people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, or asexual (LGBTQIA+), lack of acceptance from others can seriously harm mental health. According to the American Psychiatric Association, LGBTQIA+ individuals may face rejection by their family or community; discrimination in work, healthcare, or religious settings; and verbal, physical, or sexual harassment—all of which can increase the risk for anxiety. In fact, LGBTQIA+ individuals are more than twice as likely as their straight peers to have an anxiety disorder or depression.

Race and Ethnicity

White Americans tend to have higher rates of GAD, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder than other races, according to one study. But there’s a caveat: Black, Latinx or Hispanic, Asian, and Native Americans have significant barriers to care that may contribute to under- or misdiagnosis of mental health conditions. These barriers include a lack of insurance, stigma within their own communities, and a limited number of providers who are trained in how cultural identity impacts mental health. (See “The Directories,” below, for help finding a therapist who understands your culture.)

Pregnancy

These days, people are much more open about postpartum depression, but there’s little talk about the excessive anxiety that can show up for the first time during or after pregnancy. Prenatal anxiety disorder occurs in 15 percent of pregnancies, and postpartum anxiety disorder affects almost 10 percent of new mothers, according to a study in the British Journal of Psychiatry.

Age

This isn’t a cause, per se, but being younger seems to be a risk factor in developing anxiety (ya think?). A published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research—analyzing data between 2008 and 2018, before the pandemic (you know what that means!)—found that anxiety increased for all age demos under 50, with the most rapid increase in people ages 18 to 25, a near-doubling from 7.97 percent to 14.66 percent. Ouch.

Related Conditions

Anxiety disorders are connected to a handful of other mental health conditions. Symptoms may overlap, and a person can have more than one condition at a time.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

OCD is closely related to anxiety disorders. In fact, the diagnostic manual used by clinicians—called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—previously listed the condition as a type of anxiety disorder. Research shows that GAD is the anxiety disorder with the most overlap; in one 2021 study, 33.56 percent of OCD patients also had GAD.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD often develops alongside anxiety disorders, particularly social phobia. In one study published in The Psychiatric Quarterly, 36.3 percent of people with PTSD also had social phobia, and 9.8 percent had GAD. (Quick sidebar: The study also showed that PTSD was more prevalent in women than men—busting a common misconception.)

Depression

Everyone gets down at times, but people with depression have persistent sadness, loss of interest in things they usually enjoy, or feelings of hopelessness that last for two weeks or longer. Unfortunately, depression and anxiety disorders often go hand in hand—about 46 percent of people with depression also have one or more anxiety disorders in their lifetime, according to World Health Organization data.

The Best Treatments for Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders

Here’s the most important thing you should know about anxiety disorders: They are one of the most treatable mental health conditions, says Debra Kissen, Ph.D., a psychologist and spokesperson for the Anxiety and Depression Association of America. “By taking action, there’s a lot to be hopeful for, even though it doesn’t feel like it in the moment when you’re struggling with anxiety.”

There are a variety of treatments for anxiety disorders, including therapy and medication options that can be used alone or together. “The research has shown that doing both therapy and medication in combination is more effective than just doing one or the other,” Dr. Shepard notes. “Medications help the brain to see things in a less-threatening way, but to have that actually mean something, you need experiences where you can look at things in a different way, and therapy pushes you to do that.” Consider these top treatments.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

If you get bogged down by unhelpful thoughts or behaviors that fuel anxiety, CBT offers a chance to essentially retrain your brain in a span of 12 to 16 weeks. “The cognitive part of CBT focuses on identifying extreme thoughts that come with anxiety and replacing them with more accurate ones,” Dr. Kissen says.

For example: Everything’s going to be awful. I’m not going to be able to handle that. In CBT, you’ll work with your therapist to challenge that thought. Is it accurate—or distorted? Try swapping it for one that acknowledges the difficulty of the situation but also your own abilities, such as: Maybe this will be hard, but I’ve handled hard things in the past.

The behavioral part of CBT often involves learning to face your anxiety triggers rather than running from them. “Basically, you’ll teach your brain to recognize that the anxiety you’re feeling is a false alarm,” Dr. Kissen says.

Exposure Therapy

For people with social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and phobias, a particular type of behavioral therapy known as exposure therapy can help you safely confront what you fear most and break a pattern of avoidance, Dr. Nestadt says. There are different ways to do exposure therapy, but a common approach is to start with a brief, yes, exposure to your feared stimulus and gradually work your way up to longer, more intense exposures—usually over a course of 12 weekly sessions—until you’re desensitized to the object. (We realize this may sound like an episode of American Horror Story, but it works for many people, and really can for you, too.)

Say you have a fear of public speaking, but your job requires you to give occasional presentations. With exposure therapy, you might start by reading a short passage aloud to your therapist. In a later session, your therapist might ask you to do the same thing with a couple of close friends, and later on, in front of a handful of strangers. Gradually, you’ll work your way up to sharing an original presentation with a room full of people ready to ask you questions.

Exposure therapy won’t help you magically fall in love with what you fear, but over time, it can teach your brain that even though something is uncomfortable, it’s not as dangerous as you might have believed.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

If you’re interested in medication, most clinicians will typically start with SSRIs, which gradually decrease baseline anxiety, or the anxiety you feel day to day. “These medications tend to work well for most people with anxiety disorders, and they’re also the least likely of all our medicines to have side effects,” Dr. Shepard says.

How they actually work isn’t fully understood yet. There was an old theory that SSRIs basically block the reuptake of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that helps regulate mood, so that there was more available serotonin doing its thing on the brain, Dr. Shepard explains. “That probably still does play a role, but we’re also realizing that there is a role of these medicines helping to decrease inflammation in the brain and helping with something called neuroplasticity,” which is the brain’s ability to change and adapt.

This group of medications includes:

- Citalopram (Celexa)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox)

- Paroxetine (Paxil)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

“Most clinicians, unless there’s an extenuating circumstance, typically start with an SSRI if someone is interested in medication,” Dr. Shepard says. “Those medicines tend to work well for most people with anxiety disorders. They’re also the least likely of all our medicines to have side effects, so we like to go with them first if we can.”

Another perk of SSRIs: “When we see people who are anxious, many of them also have depressed mood, so it’s nice that we can treat anxiety and depression with a single medication,” Dr. Distler says.

That said, SSRIs need time and consistency to work. You may start to feel some improvement in anxiety within one to two weeks, but it can take four to eight weeks to experience the full benefit, Dr. Shepard says. It’s important to take an SSRI daily according to your doctor’s instructions, not just when anxiety is really bad. Likewise, you shouldn’t skip a dose if you feel a little better—that could be the medicine working.

Many people take SSRIs as a long-term, maintenance medication for anxiety, but in some cases you may want to switch or stop your medication. For example, if a particular SSRI is causing too many side effects—such as a decrease in libido or problems with orgasm—your doctor may recommend a different medication, or if you’re able to manage anxiety with skills you gained from CBT, you and your doctor may decide to discontinue medication.

GOTTA READ: One Woman’s Trek to Finding Her Best Anxiety-Meds Combo

Whatever the reason you want to stop an SSRI, work with your doctor to slowly and gradually do so—referred to as tapering or weaning off. Never stop taking an SSRI suddenly, which can lead to withdrawal syndrome and flu-like symptoms, Dr. Shepard says.

Benzodiazepines and Other Treatment Options

As generally safe and effective as SSRIs are, they’re not always the right or only solution for anxiety. For one, because it takes weeks for their benefits to fully kick in, they’re not helpful for acute anxiety or when you need relief, stat. Plus, though experts aren’t exactly sure why, some people simply don’t respond well to SSRIs.

This is where benzodiazepines (a.k.a. benzos), such as alprazolam (Xanax) or clonazepam (Klonopin), may come in. These powerful medications can cut through anxiety in a matter of hours or days, but they also have serious risks for dependence and abuse.

If these common therapies and medications don’t work for you, there are lots of other alternatives. Talk to your doctor about your options.

How Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders Affect Work, Love, and Friends

Parts of your anxiety disorder can be an unwelcome coworker or relationship third wheel. Take hypervigilance. You might check and recheck work emails to make sure you didn’t say anything inappropriate or miss an important message. Or if your significant other is on a long drive, you might text a few (or 10) too many times—and feel distress if you don’t hear back right away.

If irritability is part of your symptom pack, this could manifest as a short fuse during a Zoom work conference or a conversation with a parent. Then there’s excessive reassurance seeking, another sneaky way anxiety shows up. That’s when you constantly ask others around you if “you’re doing something right” or if “everything is okay,” Dr. Nestadt says. For example, you might ask friends after a party, “Did I say or do anything embarrassing?” Or you may need frequent confirmation that your romantic relationships or friendships are secure: “Are you mad at me? Is everything okay between us?” (If you’re always thinking everybody hates you—girl, we feel you.)

Undiagnosed anxiety can also add a layer of complexity. “After my first child was born, I would write everything down, like how many ounces of formula and how many wet diapers, and I did that for months and months and months,” says Walker, the graphic designer. Meanwhile, her husband seemed to slip into his new role easily. “I remember being mad at him. Like, Why is it so easy for you to be a dad, and I can’t figure out how to be a mom?“

The bright spot: With treatment, you’ll understand yourself better and learn ways to cope with anxiety when it rears its annoying head. Plus, building close relationships is one of the best ways you can help yourself if you have an anxiety disorder.

“It’s helped to not be embarrassed to talk to people that I trust about my feelings,” Weaver says. “For a long time, I was really afraid of being vulnerable—I didn’t want to tell my high school friends who I had a crush on or if I got a bad grade on a test. Now, I realize that allows me to be more connected to people and find a support system.”

3 Things You Should Never Say to People with Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders

Even if you don’t have an anxiety disorder, chances are high that a loved one might. Your support can make a big difference. If you can, learn more about the condition. But whatever you say, don’t say this.

1. “It’s all in your head—you’re fine.”

“Someone’s psychological pain is real, and it can be very uncomfortable,” Dr. Kissen says. “And by telling someone ‘you’re fine,’ it could invalidate their situation.”

Instead, say… “What you’re experiencing sounds hard and uncomfortable, and I believe in you.”

2. “You should…”

“If I’m having anxiety or having a hard thought, one thing that usually does not help is someone giving me advice on what to do,” says Weaver, the artist. “Maybe I just need a hug, or maybe I just want space, or maybe I just want to watch a show with them.”

Instead, say… “What do you need from me?” It can be hard for someone who’s feeling anxious to ask for what they need, so this can make it easier, Weaver says.

3. “Let me do that for you.”

A key part of anxiety treatment is learning to cope with, rather than avoid, anxiety triggers. Though well-intentioned, doing everything for someone with an anxiety disorder actually makes anxiety worse, Dr. Neal-Barnett says.

Instead, say… “Can I help you with that?” If someone is afraid to leave home and go to the store, for example, go to the store with them—not for them.

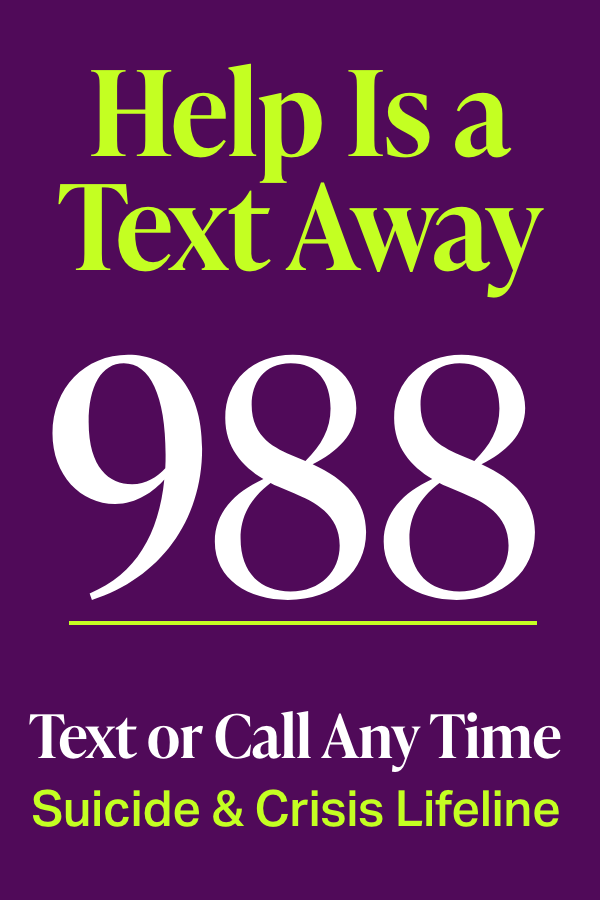

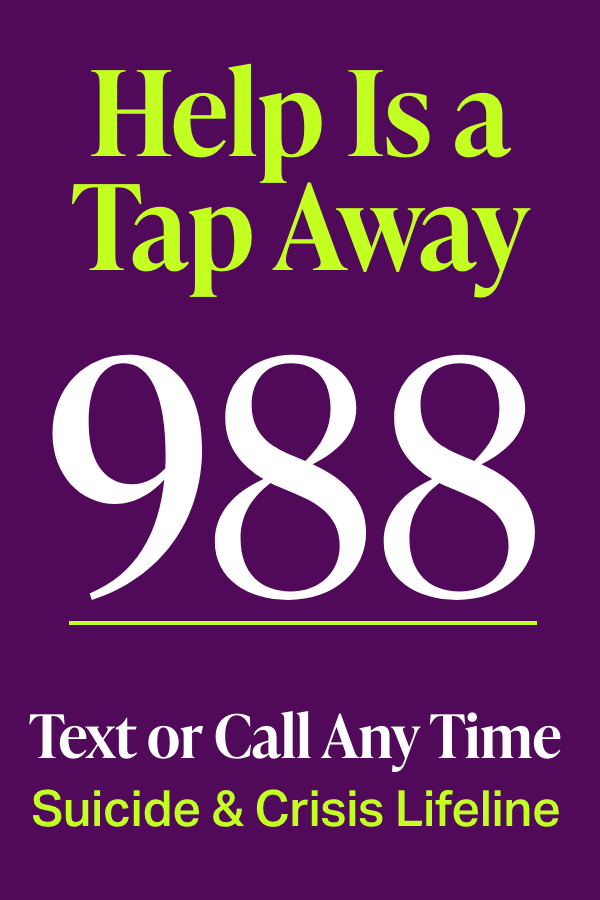

Where Can I Find Help for Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders?

To get started with treatment, the first step is to connect with a mental health professional. Check with your network. If you have health insurance and want to make sure you can use it, look up your provider network online, Dr. Kissen recommends. Can’t find availability? Call your health insurance company directly. They may be able to provide more help that way. Then check out these other avenues to support.

The Orgs

For educational information and helpful resources on anxiety disorders and mental health, give these nonprofit organizations a click.

The Directories

Expert-recommended provider directories can help you find a therapist. Most allow you to search by zip code and, if available, you can filter for therapists who treat anxiety disorders or offer virtual options.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America: Find a Therapist and Telemental Health Providers

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

- Asian Mental Health Collective

- Latinx Therapy

- Therapy for Black Girls

The Follows

The fact that anxiety disorders are the most common mental condition in the U.S. doesn’t make the experience feel any less lonely. But following these mental health advocates might.

Carolyn Rubenstein, Ph.D., @carolynrubensteinphd

Follow because: She’s not only a psychologist (and the Chief Wellness pro at Misfits Gaming) she’s a self-care pro, with lots of insights on burnout, building confidence and resilience, and stress-relief.

Kirren Schnack, Ph.D., @drkirren on IG and TikTok

Follow because: She gets specific about different anxiety issues (“death anxiety in motherhood,” cardiophobia, anxiety dizziness), so chances are, she’ll cover some of yours.

Micheline Malouf, LMHC, @micheline.maaloouf on IG and TikTok

Follow because: Her tips for coping with anxiety and panic attacks are practical—do-able. And she uses humor, a refreshing way to teach and help.

The Apps

Happify and Sanvello are anxiety-focused apps recommended by the experts at UCSF Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. They also get high marks for credibility, user experience, and transparency from One Mind PsyberGuide. Download away!

Sign up for our free newsletter

Legit tips and cool copes, delivered straight to your inbox.

By completing this form you are signing up to receive our emails and can unsubscribe anytime.

- Anxiety Statistics: What Are Anxiety Disorders? American Psychiatric Association. June 2023.

- Likely Rise of Anxiety in Young People: Goodwin RD, Weinberger AH, Kim JH, et al. Trends in Anxiety Among Adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid Increases Among Young Adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research. August 21, 2020.

- Anxiety Risk in Women: Facts. Anxiety & Depression Association of America. September 16, 2021.

- Transportation Risks: Deaths by Transportation Mode. National Safety Council Injury Facts. 2022

- Panic Attacks: Cackovic C, Nazir S, Marwaha R. Panic Disorder. StatPearls. June 21, 2022.

- Gut-Brain Connection: Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions Between Enteric Microbiota, Central, and Enteric Nervous Systems. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2016.

- Inflammatory Bowel Syndrome: Banerjee A, Sarkhel S, Sarkar R, Dhali GK. Anxiety and Depression in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. November-December 2017.

- Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Systems: Waxenbaum J, Reddy V, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System Stat Pearls. StatPearls. July 25, 2022.

- Difficulty Concentrating: Hallion L, Steinman S, Kusmierski S. Difficulty Concentrating in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: An Evaluation of Incremental Utility and relationship to Worry. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2018.

- Eye Color: Is Eye Color Determined by Genetics? MedlinePlus.

- Genetic Risk of Anxiety Disorders: Meier S, Deckert J. Genetics of Anxiety Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports. March 2019.

- Childhood Trauma: Fast Facts: Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 29, 2023.

- Children and Toxic Stress: Nelson CA, Scott RD, Bhutta ZA, et al. Adversity in Childhood is Linked to Mental and Physical Health Throughout Life. The BMJ. 2020.

- LGBTQ Mental Health Risk Factors: Stress and Trauma Toolkit for Treating LGBTQ in a Changing Political and Social Environment. American Psychiatric Association.

- LGBTQ Mental Health Statistics: Diversity and Health Equity Education: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning. American Psychiatric Association.

- Race and Ethnicity Statistics: Asnaani A, Richey JA, Dimaite R, et al. A Cross-Ethnic Comparison of Lifetime Prevalence Rates of Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. August 2010.

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Care: Mental Health Disparities: Diverse Populations. American Psychiatric Association. 2017.

- Age and Anxiety: Goodwin RD, Weinberger AH, Kim JH, et al. Trends in Anxiety Among Adults in the United States, 2008-2018: Rapid Increases Among Young Adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research. August 21, 2020.

- OCD and GAD: Sharma P, Rosário MC, Ferrão YA, et al. The Impact of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Patients. Psychiatry Research. June 2021.

- PTSD and Social Phobia: Qassem T, Aly-ElGabry D, Alzarouni A, et al. Psychiatric Co-Morbidities in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Detailed Findings from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in the English Population. The Psychiatric Quarterly. March 2021.

- Depression and Anxiety: Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Berglund P, et al. Anxious and Non-Anxious Major Depressive Disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. June 2015.

- Prenatal and Postpartum Anxiety Disorders: Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of Antenatal and Postnatal Anxiety: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. British Journal of Anxiety. May 2017.

- Neuroplasticity: Puderbaugh M, Emmady PD. Neuroplasticity. StatPearls. May 1, 2023.

- Excessive Reassurance Seeking: Rector N, Kamkar K, Cassin S, et al. Assessing Excessive Reassurance Seeking in the Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. October 2011.

- Anxiety Apps: Useful Wellness and Mental Health Apps. UCSF Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

- Anxiety Apps: Help Me Find an App. One Mind PsyberGuide.